Here, in chapter 7.4 of Autoheterosexual: Attracted to Being the Other Sex, I cover transspecies identity within the therian subculture.

When someone has a deep, integral or personal belief that they’re a nonhuman animal, it’s called therianthropy (“theri-” means “wild animal”)[i]. People who experience this are therianthropes, or therians for short[ii].

Therians often believe their connection to their inner animal side—their therioside—is spiritual or psychological in nature[iii]. They’re also likely to believe that they were born with a connection to their animal species, that they share traits with it, or that they were that species in a past life[iv]. Their animal identification may coexist with their human identity or replace it entirely[v].

A therian’s transspecies identity may be accompanied by mental suffering because of perceived differences between their ideal self and physical self[vi]. This species dysphoria can manifest as pain, discomfort, or dissatisfaction in response to this mismatch between their animal identity and their human body[vii]. Species dysphoria also manifests as emotional detachment from their human form[viii]. Some therians have even reported that suppressing their therian side has previously led to severe depression or suicidal thoughts[ix].

For therians, species dysphoria can be a powerful confirmation of their cross-species identity[x]. One therian said their dysphoria was “the single biggest reason I don’t think it’s all just a delusion”[xi]. Another saw themselves as “a wolf born into the wrong body”[xii].

By contrast, species euphoria strengthens cross-species identity by creating emotionally significant, memorable experiences. For example, when one therian heard a wolf howling just outside their tent during a childhood camping trip, they “broke out into goosebumps” and felt extremely happy and excited for days afterward[xiii].

This infatuation with wolves is common among therians. In fact, the nonhuman species to which they identify—their theriotype—is more likely to be a wolf than any other species[xiv].

As with furry fursonas, canine species are the most popular theriotypes, followed next by feline species[xv]. And if mythical creatures such as dragons count as valid theriotypes, they are the third-most common[xvi].

Pet ownership trends also follow this pattern. In the US, surveys consistently find that dogs are the most popular pet, followed by cats[xvii]. Depending on the state, approximately 40–70% of American households have pets[xviii]. One 1997 therian survey, however, found that 96% of respondents had childhood pets[xix].

Since it seems so common for therians to have had childhood pets, and their theriotypes seem congruent with broader pet-ownership trends, perhaps childhood exposure to animals influences a would-be therian’s development and alters their eventual theriotype.

Shifting

In their minds, therians hold a conception of the appearance, behavior, and consciousness of their identified species. If they perceive that their embodiment matches up with this conception, they shift toward feeling more like their theriotype.

This shift toward an animal mindstate is a therioshift, but therians usually just call it a shift. As a community, they’ve coined many terms to describe the various types of shifts they experience. These are some of the more common ones:

Mental shift—a change in mindset toward being more animal-like and less human-like, adopting a more animal outlook, feelings, or perceptions[xx]

Phantom shift—a distinct sense of having phantom animal anatomy as part of one’s body (i.e., a tail, ears, muzzle, paws, fur, four legs, scales, fins, or wings)[xxi]

Perception/sensory shift—a change in sensory perception toward being more animal-like (i.e., more attentive smell or hearing)

Cameo shift—a therioshift toward feeling like a different species of animal than one’s known theriotype(s)

Dream shift: being partly or fully an animal within a dream

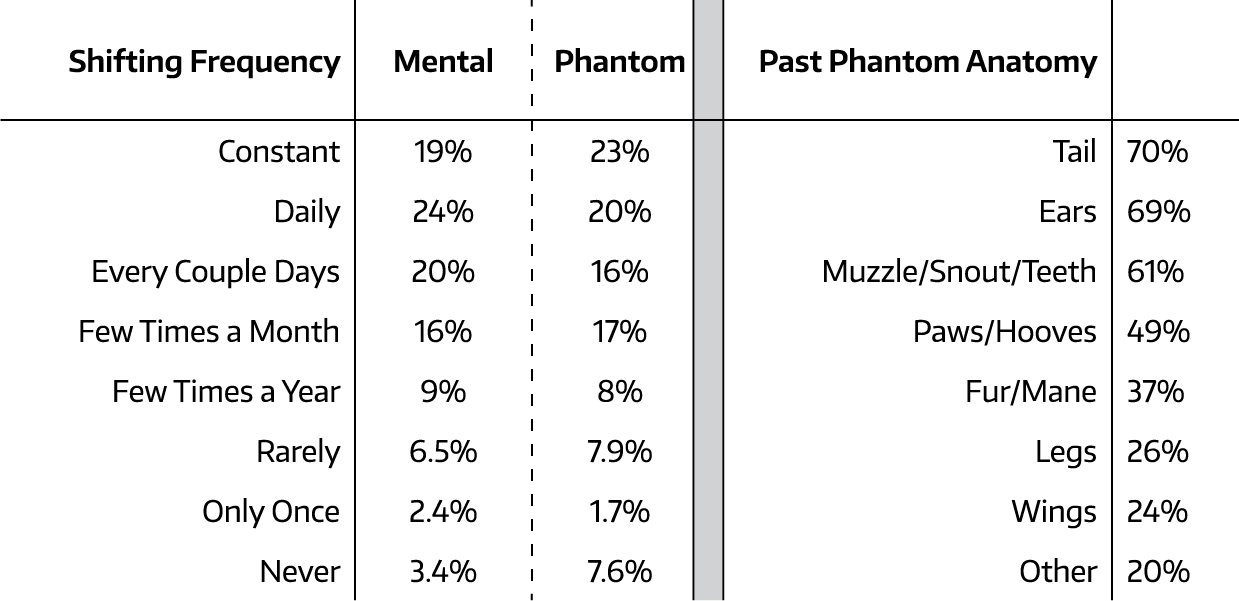

Mental shifts and phantom shifts are the most common types of shifts among therians[xxii]. The vast majority of therians have experienced both mental and phantom shifts (see Table 7.4.1).

Therian mental shifts involve embodying the consciousness of a nonhuman animal species. Most types of shifts that have been named involve changes to mental states and are thus ultimately subvariants of mental shifts.

During a mental shift, it’s common for therians to behave in a way that more closely resembles their idea of how their animal species behaves. For instance, a wolf therian might walk on all fours, howl, or get the urge to chase someone down as if they were prey.

During a phantom shift, therians experience the sensation of having nonhuman body parts as part of their body. These are usually the same features that their theriotype has, so these can help therians figure out their theriotype, or that they’re even therian in the first place[xxiii]. Therians are usually a species with tails, ears, and paws, so these are some of the most common features for therians to experience during phantom shifts (see Table 7.4.1).

Shifting isn’t limited to charismatic megafauna such as wolves, jaguars, and dragons, either. An earwig therian can experience it too:

When it told me via trances, dreams, mirror-talks, and other rather terrifying (at the time) means, that it was moving into my consciousness, I was scared. I thought I was going absolutely insane. I fought it tooth and nail, and yet I could feel that armour plating begin coming up, snapping into place, in daily life…but my inner voice would keep going: “you are strong, you have discovered a part of you that was hidden away for (family, society, self)’s sake. Now, you can be twice as strong, for though you are small, you are fast, you have self-defence.”[xxiv]

Unintentional shifts like this can feel more like instincts, thereby strengthening a therian’s cross-species identity[xxv]. These unconsciously induced shifts are known as “involuntary shifts”, whereas consciously induced shifts are “voluntary shifts”.

As therians learn what triggers their shifts, they can gain more control over when and where they shift. By embodying their theriotype through voluntarily shifting at appropriate times and places, therians can reduce their feelings of species dysphoria[xxvi].

In order to trigger a shift, therians may choose to meditate, surround themselves with nature, behave like their species, or interact with objects associated with their species[xxvii]. For example, one former therian reported that donning a full wolf skin “invariably brings on a strong mental shift”[xxviii]. However, some therians can shift without needing any specific rituals or environments to induce it[xxix].

Perhaps because so many therians identify as wolves, some of them report that a full moon can increase their shifting ability, cause emotional changes, or increase their sex drive[xxx]. One therian referred to this species euphoria as a “moon buzz” and noted that it paradoxically caused a restless, manic energy in some therians yet brought calmness to others[xxxi].

Some therians don’t shift in a binary fashion between human and animal. Instead, they exist on a spectrum between animal and human, fluidly wavering between the two[xxxii].

Transspecies identity can also be a permanent state of being. Online surveys of therians have found that about one in five report a “constant” mental shift, and slightly more report a “constant” phantom shift (see Table 7.4.1)[xxxiii].

If the frequency of shifting that therians report is typical among people with autosexual trans identities, then the vast majority of autohet transgender people also experience shifts, with most doing so at least a couple times a week.

Different types of shifts are likely to have different impacts on feelings and identity. Phantom shifts create the sensation of phantom anatomy and thus can contribute to anatomic dysphoria. Similarly, mental shifts can make someone feel they have the consciousness of a particular type of entity, a sensation that is likely behind the internal sense of identity reported by people with various forms of trans identity.

When I first encountered the concept of shifting, it was a eureka moment for me. I saw it as a conceptual breakthrough that could help autosexuals interpret and speak about their cross-identity experiences more effectively. By creating and developing the concept of shifting, the therian community has made a great contribution to the broader autosexual population.

Zoophilia—Sexual Attraction to Animals

If therianthropy is caused by an erotic target identity inversion, then we should expect therians to report sexual attraction to animals (zoophilia) as well as sexual attraction to being an animal (autozoophilia).

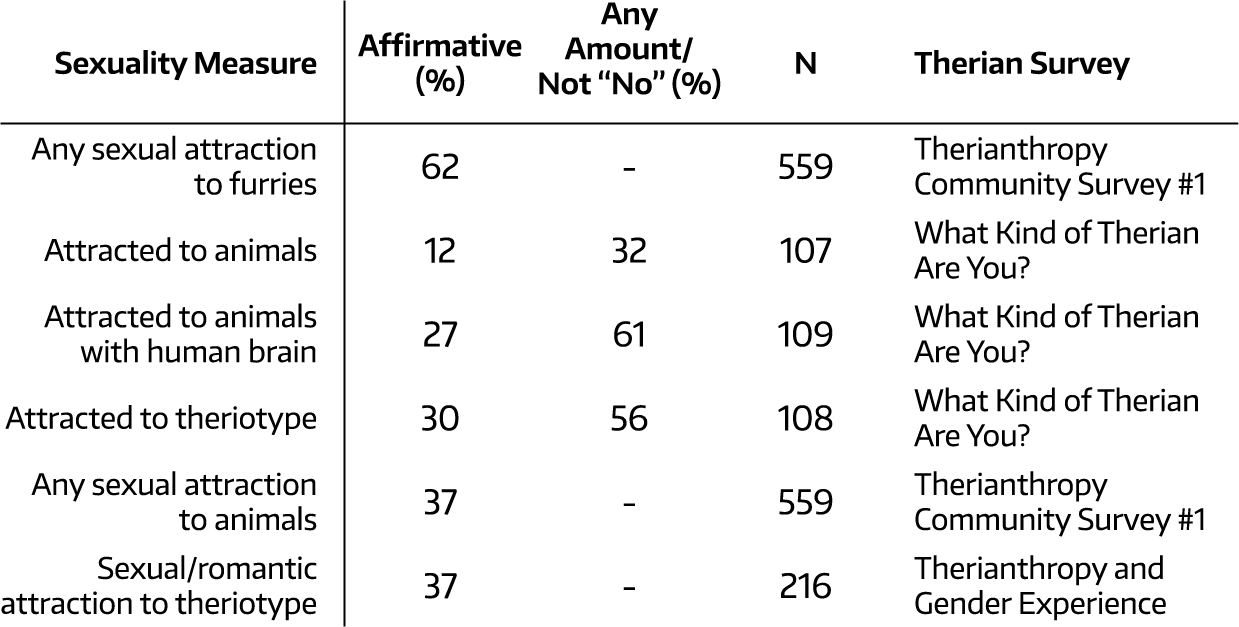

As expected, therians are sexually attracted to animals at uncommonly high rates. In community surveys[xxxiv], about a third of therians admit they are attracted to animals[xxxv], and a higher proportion don’t deny being attracted to animals (see Table 7.4.2).

Studies of other populations find much lower rates of zoophilia. A Quebec-based study of sexual fantasies found that 2–3% of people had previously fantasized about having sex with an animal[xxxvi], and a study of male college students found that 5.3% of them had previously fantasized about animals during sexual intercourse[xxxvii]. Similarly, a representative survey of the Czech population found that 4% of males and 2% of females reported at least some zoophilic preference[xxxviii].

The proportion of therians who admit to zoophilic attractions far surpasses that of more general populations. Even if not all therians are willing to report sexual attraction to animals, enough do that it’s reasonable to infer an enduring pattern of attraction to animals plays a role in their cross-species identity.

This sexual-orientation-based explanation for therianthropy also makes sense of some of therianthropy’s other aspects:

Many therians report knowing of their animal nature their whole life, or at least since childhood

Therians are likely to believe that therianthropy (or the capacity to develop it) is an inborn trait[xxxix]

They commonly discover their animal nature “around the ages 10-16 or whenever puberty starts”[xl]

Emulating animals leads to “special comfort and feelings of naturalness”[xli]

These are the same sorts of beliefs and feelings reported by people with other autosexual orientations. The developmental timelines are also similar, as are the catalyzing effects of puberty.

Another curious similarity is that therians are more likely to have autism or mental health issues. One study comparing therians to non-therians found that therians were about six times as likely to show high levels of autistic traits and three to four times as likely to have been previously diagnosed with a mental health issue[xlii]. These elevated rates of autism and mental health diagnoses closely resemble those found among transgender people (see Chapters 4.2 and 4.3).

Data on zoophilia and autozoophilia from Hsu and Bailey’s study of male furries also supports the idea that autozoophilia is an erotic target identity inversion. The correlation they found between zoophilia and autozoophilia (r = 0.48) was about as strong as the one they found between gynephilia and autogynephilia (r = 0.44)[xliii].

In the course of writing this chapter, I didn’t find any formal research on therians that estimated how many of them are sexually attracted to being an animal. The results from therian and otherkin community surveys shown in the next chapter, however, suggest that it’s common for therians to be their theriotype in their sexual fantasies or enjoy being treated as their theriotype in sexual contexts.

In Sum:

Therians are people who feel a deep psychological or spiritual connection to a real, nonhuman animal species. Many of them identify as that species of animal.

Therians can feel pain, discomfort, or dissatisfaction in response to the mismatch between their nonhuman animal identity and their human body. This species dysphoria can make them feel detached or alienated from their human form, and may serve as confirmation that they are truly therian.

Therians created the concept of shifting to describe their experiences of cross-embodiment. The most common types of shifts are mental shifts and phantom shifts. For therians, mental shifts create a sense of having animalistic consciousness, and phantom shifts create a sense of having phantom anatomy such as fur, four legs, or a tail. These shifts, which usually correspond to their theriotype, help reduce species dysphoria by conferring a sense of animalistic embodiment.

Many therians report knowing of their animal nature for all or most of their life, and they are likely to believe being therian is an inborn trait. They experience species euphoria by emulating animals, and they commonly discover their animal nature around the onset of puberty. They are also sexually attracted to animals at uncommonly high rates. Taken together, these traits and developmental patterns suggest that therianthropy is linked to autosexuality.

Speak With Me

Are you an autosexual person who wants to discuss your experiences with someone who actually understands what it’s like? Are you in a relationship with an autosexual person and want to understand them better? Sign up to speak with me! I’m available to speak via Zoom or phone.

[i] “Therianthropy.”

[ii] Bricker, “Life Stories of Therianthropes,” 1.

[iii] Plante et al., “FurScience! A Summary of Five Years of Research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project,” 115; Lupa, A Field Guide to Otherkin, 118.

[iv] Gerbasi et al., “Furries from A to Z (Anthropomorphism to Zoomorphism),” 216.

[v] Bricker, “Life Stories of Therianthropes,” 1.

[vi] Bricker, 34.

[vii] Bricker, 10.

[viii] Robertson, “The Beast Within,” 18.

[ix] Grivell, Clegg, and Roxburgh, “An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Identity in the Therian Community,” 125.

[x] Grivell, Clegg, and Roxburgh, 122.

[xi] Bricker, “Life Stories of Therianthropes,” 35.

[xii] Grivell, Clegg, and Roxburgh, “An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Identity in the Therian Community,” 122.

[xiii] Bricker, “Life Stories of Therianthropes,” 41–42.

[xiv] White Wolf, “2013 Therian Census,” 25.

[xv] Clegg, Collings, and Roxburgh, “Therianthropy,” 407; Lupa, A Field Guide to Otherkin, 35,280; White Wolf, “2012 Therian Census”; White Wolf, “2013 Therian Census.”

[xvi] Clegg, Collings, and Roxburgh, “Therianthropy,” 408; White Wolf, “2012 Therian Census”; White Wolf, “2013 Therian Census.”

[xvii] Applebaum, Peek, and Zsembik, “Examining U.S. Pet Ownership Using the General Social Survey”; Plotts, “Pet Ownership Statistics by State, And So Much More (Updated 2020)”; Marx et al., “Demographics of Pet Ownership among U.S. Adults 21 to 64 Years of Age,” 34.

[xviii] Plotts, “Pet Ownership Statistics by State, And So Much More (Updated 2020).”

[xix] Utlah, “AHWW Poll ’97.”

[xx] Robertson, “The Beast Within,” 20.

[xxi] Robertson, 20.

[xxii] White Wolf, “2013 Therian Census,” 38–42.

[xxiii] Bricker, “Life Stories of Therianthropes,” 39–40.

[xxiv] Robertson, “The Beast Within,” 20.

[xxv] Bricker, “Life Stories of Therianthropes,” 41.

[xxvi] “Mental Shift.”

[xxvii] Lupa, A Field Guide to Otherkin, 128.

[xxviii] Lupa, 128.

[xxix] Lupa, 128.

[xxx] Utlah, “AHWW Poll ’97”; White Wolf, “2013 Therian Census.”

[xxxi] Utlah, “AHWW Poll ’97.”

[xxxii] “Vacillant Therianthropy | Therianthropy | Fandom.”

[xxxiii] White Wolf, “2012 Therian Census,” 25,26; White Wolf, “2013 Therian Census,” 41,42.

[xxxiv] Asikaa, “The Great AHWW Survey!”; Utlah, “AHWW Poll ’97”; PinkDolphin, “Fluid Identity & Experiences within Therianthropy 2020”; White Wolf, “2012 Therian Census”; White Wolf, “2013 Therian Census”; Reddit user: u/mithril-animal, “Therian Community Survey #1”; PinkDolphin, “Therianthropy and Gender Experience”; Citrakāyaḥ, “Werelist Poll of 2013”; Reddit user: u/40-I-4-Z-Kalisza, “What Kind of Therian Are You?”

[xxxv] Reddit user: u/40-I-4-Z-Kalisza, “What Kind of Therian Are You?”; PinkDolphin, “Therianthropy and Gender Experience”; Reddit user: u/mithril-animal, “Therian Community Survey #1.”

[xxxvi] Joyal, Cossette, and Lapierre, “What Exactly Is an Unusual Sexual Fantasy?,” 334.

[xxxvii] Crepault and Couture, “Men’s Erotic Fantasies,” 572.

[xxxviii] Bártová et al., “The Prevalence of Paraphilic Interests in the Czech Population,” 5.

[xxxix] Robertson, “The Beast Within,” 17.

[xl] “F.A.Q.s — The Therian Guide.”

[xli] Bricker, “Life Stories of Therianthropes,” 28.

[xlii] Clegg, Collings, and Roxburgh, “Therianthropy,” 414.

[xliii] Hsu and Bailey, “The ‘Furry’ Phenomenon,” 12.

That's crazy because, as a child, I always seemed to shift away from anything that had to do with people to the point where my pre-K teacher noticed I tended towards self-isolation. Not to mention, I always preferred stuffed animals over dolls since the latter made me sad and uncomfortable for some reason. But, discovering my libido at 7/8 years old manifested in a combination of autozoophilia, zoophilia, and AAP where the fantasies would be heterosexual in nature. This sexuality was mostly triggered by videos I had stumbled upon over the internet, but I fear my inhibition towards other people that I mentioned before played a part in allowing this to develop. Over time, however, my sexuality began to wane and it eventually disappeared from my fantasies (although, I tend to gravitate towards imagining alpha/omega dynamics and the anatomy that comes with that).

I should also note that I was very attached to animals and their essence as a child where I enjoyed roleplaying as them -- this was mostly online as I got older, but there was a time in elementary school I crawled around the schoolyard on all-fours with a polymer cheetah in my mouth as I pretended to be its mother (which I got looks for lol). In addition, I enjoyed "shifting" mentally into a more animal-like state as it gave me comfort. Even today, I still feel a dissatisfaction with my body and a feeling that I don't belong in it -- also a bad habit of walking on my toes that I never seemed to kick (unconsciously trying to imitate hocks, maybe, or just wanting to feel "graceful"). But, it should be stated that I have severe BDD that I suffered with for many years and any association with feeling out-of-body likely stems from this crippling insecurity and a strong fear of rejection/aversion to strangers that was fueled by my parents' paranoia.

I need to mention that I don't have autism (or I'm 90% sure I don't) and that I feel I was simply at the wrong place at the wrong time. This article was enlightening, though, and made me feel less alone, so thank you!