Autoheterosexual and homosexual preferences occur at similar rates, yet there is a huge imbalance in awareness about these two sexual orientations.

Where does this imbalance come from? Why is homosexuality mainstream knowledge while autoheterosexuality is comparatively unknown?

A lot of this imbalance originates in differences between allosexuality and autosexuality. Allosexuality motivates sexual union with other people, which drives an external search for compatible sexual partners.

Gay people need to find each other in order to fulfill their sexual and romantic needs. They often move to cities big enough to support community infrastructure (i.e., gay bars), which helps gay people develop a shared identity and become visible to broader society.

In contrast, autosexuality can exist in isolation, as a closed loop. It doesn’t require others.

In the past, autohets typically formed heterosexual partnerships and participated in society as their default-gender selves while keeping their cross-gender selves confined to their homes. However, the recent cultural ascendance of transgenderism has changed the game: it’s safer than ever for autohets to express their cross-gender selves in public.

Exactly How Many Autoheterosexuals Are There?

Depending on how researchers find study participants and ask them questions, they arrive at different estimates of the prevalence of autoheterosexuality.

These estimates tend to be on the higher side when researchers ask “have you ever” questions, because even one recalled instance of cross-gender arousal, behavior, or fantasy gets recorded as a “yes”. Similarly, questions about sexual fantasies tend to get more “yes” responses than questions about past experience, because people don’t always act on their fantasies.

Some small studies on college undergrads[1] found autoheterosexuality or erotic transvestism prevalence rates anywhere from just a few percent all the way up to 15%. A recent online study of more than 4,000 people found that 15% of females and 25% of males reported at least a bit of sexual interest in behaving or dressing like the other sex[2].

We can best interpret double-digit estimates like these as indicators of the number of people who have a touch of cross-gender sexuality or can at least see the appeal. However, the number of people who are definitively into erotic crossdressing or cross-gender fantasy is certainly lower.

Since “transvestite” used to be the technical term for trans people, many researchers thought that the act of crossdressing itself was what mattered. They didn’t realize they were witnessing autoheterosexuality and that crossdressing was just one of many ways to symbolically evoke the idea of being the other sex.

As a result, researchers often asked study participants about crossdressing and neglected to ask about crossdreaming (imagining oneself as the other sex). Unfortunately, this approach underestimates autoheterosexuality rates in females because they tend to be less interested in transvestism.

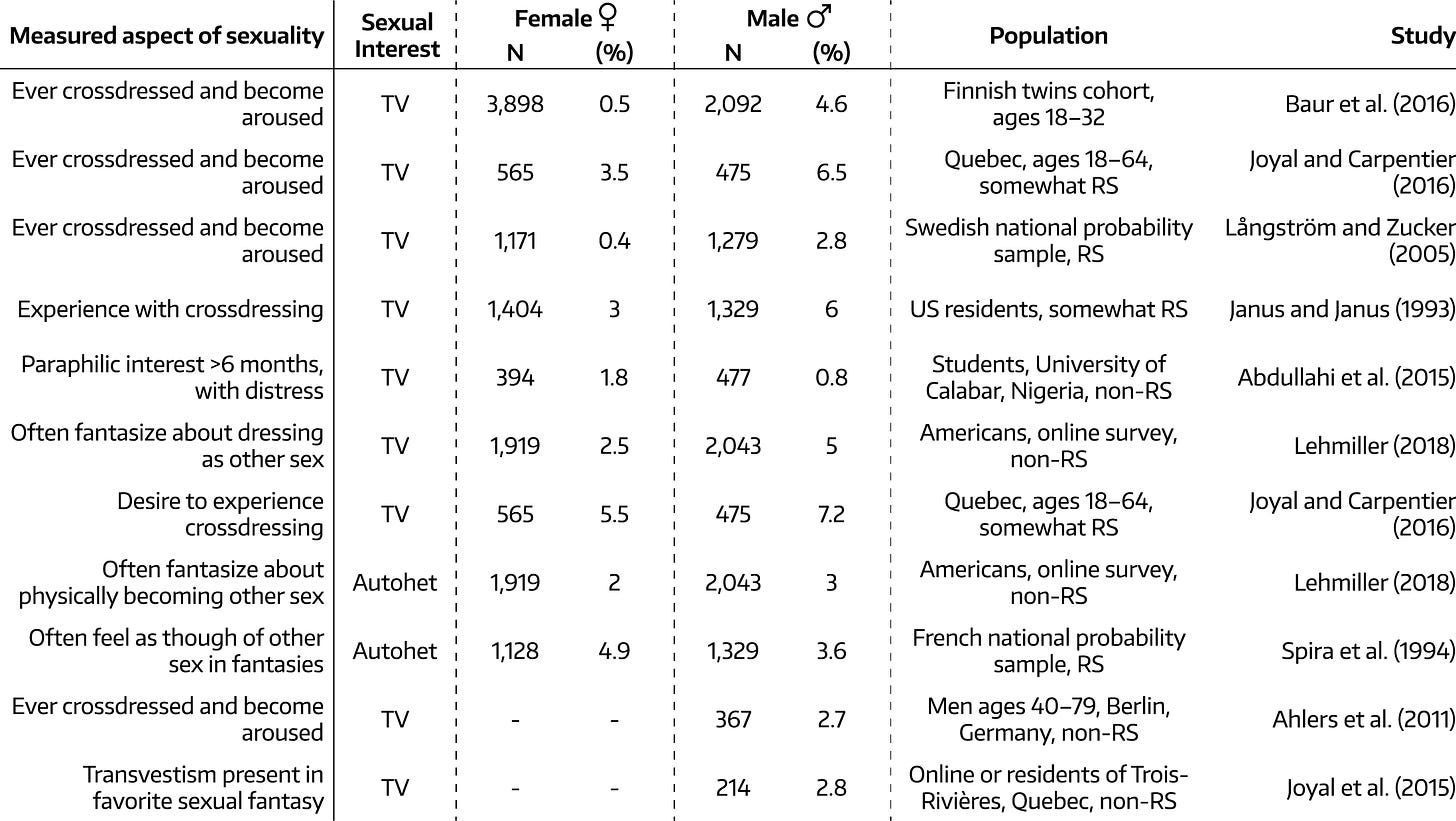

Since prevalence estimates of crossdressing and crossdreaming vary so widely between studies, I’ve collected some figures from formal studies and presented them in Table 5.0.1 to make them visible at a glance[3].

Only a couple of these studies asked about crossdreaming. Of these, one surveyed a representative sample of the French population and found that 4.9% of females and 3.6% of males often felt as though they were the other sex during sexual fantasies[4]. The other was conducted on an online sample by Justin Lehmiller for his book, Tell Me What You Want [5]. In Lehmiller’s sample, approximately 2% of females and 3% of males often fantasized about physically becoming the other sex[6].

In these two studies, sex differences in crossdreaming prevalence are rather small. But the transvestism prevalence estimates in Table 5.0.1 suggest that sex differences in crossdressing are greater. I calculated weighted averages from these estimates and found that approximately 4–5% of males have been aroused by or are sexually interested in crossdressing, whereas less than 2% of females are into erotic transvestism and less than 1% have experienced past arousal from crossdressing.

This data suggests that females and males differ more with respect to transvestism than they do with respect to cross-gender fantasy itself.

The Czech Autohet Prevalence Estimates

In early 2020, Czech sexual researchers published the biggest study to-date on the population prevalence of nonvanilla sexual interests in a representative sample of a country’s population[7]. It had over 10,000 participants.

These researchers were thorough—they collected data for five dimensions of sexuality: preference, arousal, behavior, porn use, and fantasy. Since definitions of sexual orientation often include the element of preference[8], I will call upon their figures for sexual preference.

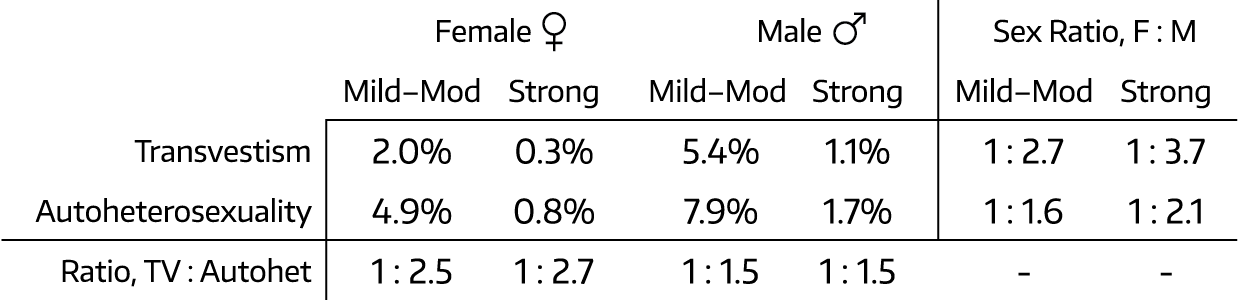

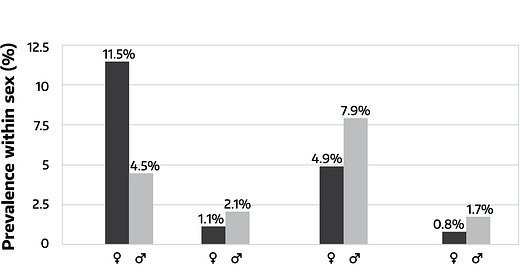

These Czech researchers presented the prevalence of transvestism and autoheterosexuality at two different levels of intensity, which I’ll categorize as “mild-moderate” and “strong”.

Due to the size and quality of this Czech sample and the care researchers took to differentiate among different strengths of sexual interest, I consider these prevalence estimates for autoheterosexuality to be the most reliable, so all further calculations in this book that rely on autohet prevalence estimates will use them.

In Table 5.0.2, I’ve listed the transvestism and autoheterosexuality prevalence estimates from this study along with ratios inferred from them. These ratios help illuminate how females and males differ with respect to imagining themselves as the other sex (crossdreaming) and its sartorial expression (crossdressing).

In comparison to females, males were more likely to have a sexual preference for crossdressing or crossdreaming. This sex difference was even more apparent when it came to strong preferences, which were even more likely to happen in males.

In both females and males, sexual preferences for crossdreaming were more common than sexual preferences for crossdressing. This is what we should expect to see if sexually-motivated crossdressing is ultimately a downstream effect of autoheterosexuality which occurs in a subset of autohets.

Although females were about half as likely to have strong autoheterosexual preferences, this is still far too common to deny that female autoandrophilia exists, or that it plays a major role in FTM transsexualism.

Comparing Autoheterosexual and Nonheterosexual Prevalence

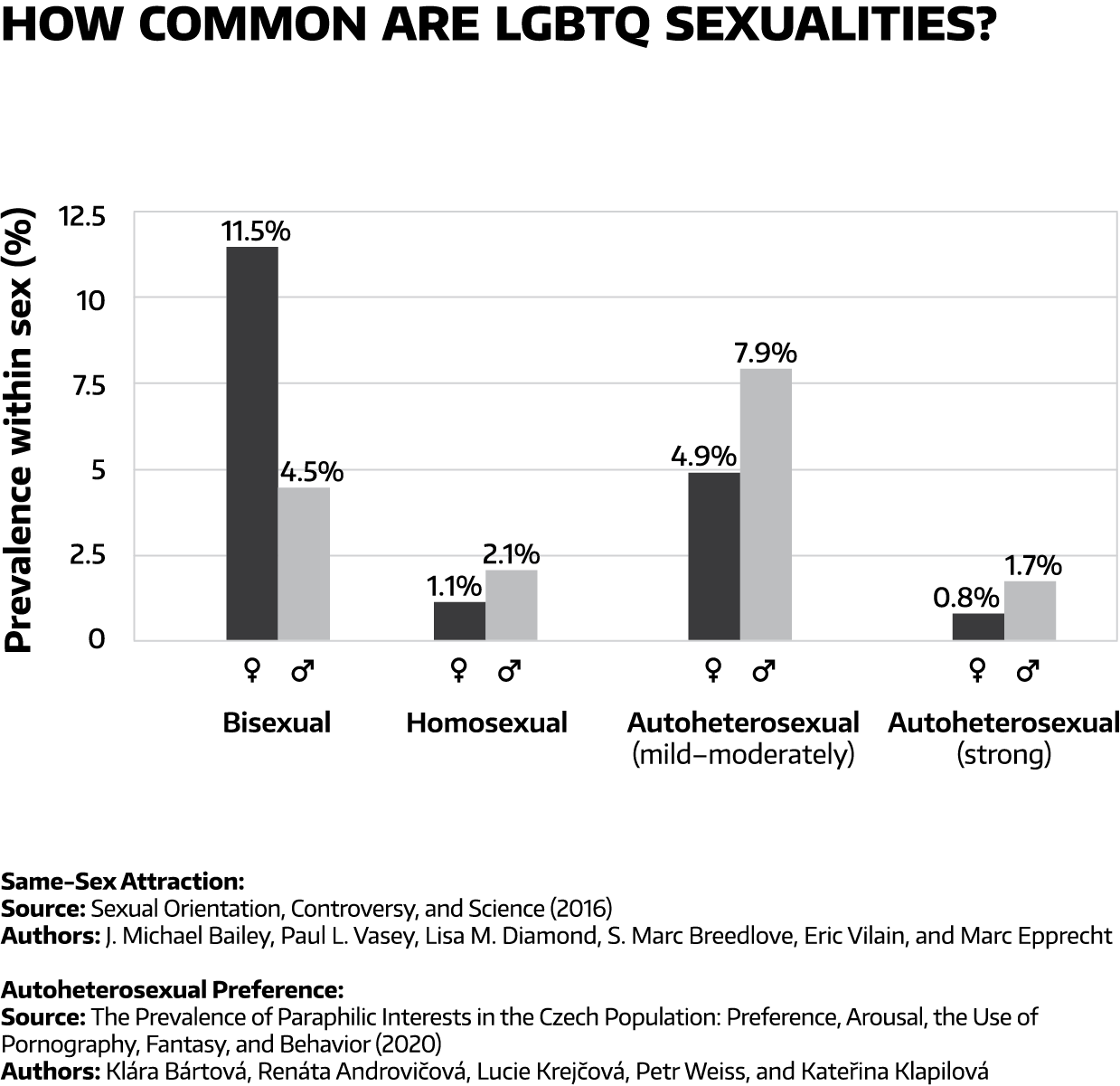

In order to estimate the size and composition of the broader etiological population from which almost all transsexuals originate, I’ll use the findings of the Czech study[9] in tandem with sexual orientation prevalence estimates from the US[10].

Both of these sources used a five-point scale. In the Czech study, 1 indicated no interest, 2 to 3 was mild to moderate interest, and 4 to 5 was strong interest[11]. From the US sexual orientation prevalence estimates[12], I’ll treat “completely heterosexual” as no same-sex attraction, “mostly heterosexual” and “bisexual” as mild to moderate levels of same-sex attraction, and “mostly homosexual” and “completely homosexual” as strong levels of same-sex attraction.

This method isn’t perfect and arguably has its flaws. For example, a bisexual person could be strongly attracted to both sexes equally, so this method of interpretation would not capture their degree of same-sex attraction adequately. However, attraction to one sex is usually associated with weaker attraction to the other, so this potential flaw isn’t a deal-breaker.

Another limitation is that I’m comparing estimates from one Eastern European country with estimates from all over the United States, a country with more cultural and genetic diversity. European ancestry is quite prevalent in the US, though, so there will still be significant genetic overlap.

Despite these limitations, I’m using these studies because they use large samples of the general population and they differentiate among five degrees of sexual interest in ways that allow for reasonable comparison between nonheterosexuality and autoheterosexuality.

Within both sexes, there are roughly three autoheterosexuals for every four homosexuals. Males are about twice as likely to be autoheterosexual or homosexual. Females are much more likely to report bisexuality, and males are more likely to report some autoheterosexuality.

Using these prevalence rates and assuming a population that is half female and half male, I’ve estimated the size of the broader etiological population from which transsexuals originate, as well as the theoretical size limit of the gender-based part of the LGBTQ coalition.

According to the two-type model, transsexuals are either homosexual or autoheterosexual. Assuming that only people who are strongly homosexual or autoheterosexual have enough gender issues to become transsexual, the broader etiological population from which transsexuals originate is approximately 2.9% of the population.

As I pointed out previously, membership within the gender-based part of the LGBTQ coalition depends on two sexual propensities: same-sex sexuality or autoheterosexuality (nonhet or autohet).

After adding up everyone who has even just a bit of same-sex attraction or autoheterosexuality, it seems that the LGBTQ coalition comprises up to about 17% of the population—one in six people. (I say “up to” because this method will double-count autohets with nonheterosexual partner preferences, and not everyone with these orientations considers themselves part of the LGBTQ coalition).

Nonheterosexuals represent just under 10% of the population, and people with any degree of autoheterosexual interest represent 7–8% of the population. The numerical wisdom of appending TQ to LGB is clear: doing so greatly increases the number of people included in the coalition.

Autoheterosexuality and Same-Sex Attraction

It is unknown exactly how many homosexuals and bisexuals owe their same-sex attraction to autoheterosexuality instead of conventional same-sex attraction, but it’s clear that some do. This is especially clear for bisexuals.

As seen in the preceding section, an estimated 4.5% of males and 11.5% of females in the US report they are either bisexual or mostly heterosexual[13].

However, bisexuality is way more common in autohets. Among people who admit to even the slightest bit of sexual interest in dressing or behaving as the other sex, an estimated 30% of males[14] and 48% of females[15] identify as bisexual.

Transgender Americans have high rates of bisexuality, too. In the 2015 US Transgender Survey, more than half of nonhomosexual trans people reported sexual identities indicative of bisexuality such as “queer”, “pansexual”, or “bisexual”[16].

What could be causing these high rates of bisexuality?

Meta-attraction is one potential source of this increased bisexuality. Attraction to androgyny is another. Both sexual propensities are common among autoheterosexuals, and both are associated with bisexuality.

Using the method described in this footnote[1], I estimated that among Americans who report bisexual or mostly heterosexual attractions, approximately one-fifth of females and three-fifths of males ultimately do so because of autoheterosexuality. If these estimates are close to the mark, it’s quite possible that autoheterosexuality is involved in most cases of male bisexuality.

Relatedly, Israeli researchers found that among people who identified as bisexual or mostly heterosexual, there were positive associations between same-sex attraction and cross-gender sentiments such as feeling like the other sex or wanting to be it[17]. This connection was present in both sexes, but noticeably stronger in males. These bi and mostly het males also reported a greater desire to be the other sex than other groups.

Although autoheterosexuality is more often associated with bisexuality than preferential homosexuality, it occurs in some people with same-sex preferences, too. For example, in that same autosexuality study which found high rates of bisexual identity among autoheterosexuals[18], approximately one in six autohet females reported greater attraction to females, and approximately one in twenty-five autohet males reported greater attraction to males.

This finding isn’t a fluke. Other researchers have documented similar overlaps between autoheterosexual interest and homosexual preference. For example, autoandrophilia is more common among lesbians than the broader female population[19]. Similarly, studies of trans women have consistently found that a proportion of those who get categorized as homosexual report past experience of autoheterosexual arousal[20].

In Sum:

Depending on the study, prevalence estimates of autoheterosexuality vary widely. Online surveys commonly produce double-digit estimates, but representative surveys generally indicate that about 3–6% of people have sexual interest in crossdressing or crossdreaming. Females tend to be on the lower end of this range, while males tend to be on the higher end.

When it comes to strong sexual preferences, there are about three autoheterosexuals for every four homosexuals. Males are approximately twice as likely to be autoheterosexual or homosexual. Females are more likely to be bisexual, but less likely to show sexual interest in crossdressing.

Autoheterosexuality is a significant contributor to bisexuality. Much of this contribution stems from attraction to androgyny and meta-attraction—both are common among autohets and both contribute to bisexuality. Much of male bisexuality, perhaps most, is ultimately autohet-related. A smaller proportion of female bisexuality is autohet-related.

In both sexes, some people with homosexual preferences are autoheterosexual. This overlap is more common in females.

Speak With Me

Are you an autosexual person who wants to discuss your experiences with someone who actually understands what it’s like? Are you in a relationship with an autosexual person and want to understand them better?

[1] In order to estimate the proportion of bisexuality associated with autoheterosexuality, I applied the bisexual identification rates in people who reported any amount of behavioral or sartorial autoheterosexuality from Brown et al. 2019 (30% of females, 48% of males) to the proportion of Czech people who reported some degree of preference for autoheterosexuality from Bartova et al. 2020 (9.6% of males, 5.7% of females). I used the prevalence estimates of bisexual and mostly heterosexual attraction from Bailey et al. 2016 (4.5% of males, 11.5% of females) as the baseline rates found in the general population.

In line with the leading etiological theory that suggests the cause of autoheterosexuality is a variation in the “where” of sexual attraction rather than the “what” (see Chapter 7.0), I assumed that 1) autoheterosexuals have the same rate of non-autohet-related bisexuality as the general population, and 2) elevated rates of bisexuality among autoheterosexuals can be attributed to autoheterosexuality itself.

This approach has various methodological flaws because it compares studies with population-representative samples to one that doesn’t, in addition to assuming that there aren’t significant differences in autohet prevalence between Americans and Czechs. Those caveats aside, this was the least bad approach I could think of with the resources available, and it’s just a starting point.

[1] Person et al., “Gender Differences in Sexual Behaviors and Fantasies in a College Population”; Hsu et al., “Gender Differences in Sexual Fantasy and Behavior in a College Population.”

[2] Brown, Barker, and Rahman, “Erotic Target Identity Inversions Among Men and Women in an Internet Sample.”

[3] Baur et al., “Paraphilic Sexual Interests and Sexually Coercive Behavior”; Joyal and Carpentier, “The Prevalence of Paraphilic Interests and Behaviors in the General Population”; Joyal, Cossette, and Lapierre, “What Exactly Is an Unusual Sexual Fantasy?”; Långström and Zucker, “Transvestic Fetishism in the General Population”; Janus and Janus, The Janus Report on Sexual Behavior; Abdullahi, Jafojo, and Udofia, “Paraphilia Among Undergraduates in a Nigerian University”; Lehmiller, “Tell Me What You Want”; Spira and Bajos, Sexual Behaviour and AIDS; Ahlers et al., “How Unusual Are the Contents of Paraphilias?”

[4] Spira and Bajos, Sexual Behaviour and AIDS.

[5] Lehmiller, “Tell Me What You Want.”

[6] Lehmiller to Illy, “Re: Fantasy Survey Stats Request- AGP/AAP, TV, + GAMP,” October 13, 2021.

[7] Bártová et al., “The Prevalence of Paraphilic Interests in the Czech Population.”

[8] Seto, “The Puzzle of Male Chronophilias,” 1.

[9] Bártová et al., “The Prevalence of Paraphilic Interests in the Czech Population.”

[10] Bailey et al., “Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science,” 55.

[11] Bártová et al., “The Prevalence of Paraphilic Interests in the Czech Population,” 3–4.

[12] Bailey et al., “Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science,” 55.

[13] Bailey et al., 55.

[14] Brown, Barker, and Rahman, “Erotic Target Identity Inversions Among Men and Women in an Internet Sample,” 5.

[15] Brown, Barker, and Rahman, 6.

[16] Grant et al., “Injustice At Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey,” 18; James et al., “The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey,” 246.

[17] Jacobson and Joel, “An Exploration of the Relations Between Self-Reported Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation in an Online Sample of Cisgender Individuals,” 13.

[18] Brown, Barker, and Rahman, “Erotic Target Identity Inversions Among Men and Women in an Internet Sample,” 5.

[19] Tailcalled, “Lesbian Autoandrophilia?”

[20] Blanchard, “Typology of Male-to-Female Transsexualism”; Nuttbrock et al., “A Further Assessment of Blanchard’s Typology of Homosexual Versus Non-Homosexual or Autogynephilic Gender Dysphoria”; Lawrence, “Sexuality Before and After Male-to-Female Sex Reassignment Surgery.”

I loved this article. I'm a few months into transitioning and so much information here shined light in dark places in my own head. Thank you x <3