This is the furry chapter from Autoheterosexual.

Humans aren’t the only beings with four limbs, a torso, and a face with two eyes, a nose, and a mouth. Canines and felines have those features, too. So do mythical creatures such as dragons, faeries, and angels.

Perhaps because of these fundamental similarities, people have the capacity to find those animals and mythical creatures sexually attractive. When those animals and mythical creatures have anthropomorphic (human-like) characteristics, people are even more likely to find them attractive.

And of course, a subset of people who are attracted to various nonhuman entities are also attracted to the idea of being one. People like this tend to fall into one or more of these three groups:

Furry fandom—a community of people who share an interest in depictions of animals that have human-like physical or mental characteristics; members of this group and the animals they depict are known as furries, or furs

Therians—people who feel a deep, integral spiritual or psychological connection to a nonhuman animal, often to the point of identifying as that animal

Otherkin—people who identify as not entirely human, often as mythical or imaginary species (i.e., dragons, angels, fairies, elves, Pokémon, etc.)

People in these groups often have a sexual interest in nonhuman creatures. Some even identify as nonhuman. Those who do are alterhuman.

Alterhuman is an umbrella term for nonhuman identification that encompasses anyone who experiences “an internal identity that is beyond the scope of what is traditionally considered ‘being human’”[i]. People who identify as wolves, tigers, dragons, angels, vampires, or elves are all alterhuman.

Many of these forms of identity are examples of cross-species identity—a form of trans identity more commonly known as transspecies identity.

People with transspecies identities can experience positive mood shifts (species euphoria) in response to stimuli that evoke a sense of cross-species embodiment. In turn, they can experience negative mood shifts (species dysphoria) in response to perceived shortcomings of animal embodiment.

These shifts in mood may occur in tandem with mental shifts that evoke a sense of having animal consciousness, or phantom shifts that create the sensation of phantom body parts such as paws, wings, or a tail. Both mental shifts and phantom shifts strengthen transspecies identity.

Although furries, therians, and otherkin are distinct groups, they have overlapping membership. Approximately 20% of furries identify as therian[ii], and roughly 5% identify as otherkin[iii].

Of these groups, furries are the largest and most well-known. Furry sexuality has also been studied more intensely than therian sexuality or otherkin sexuality, so let’s start there.

Yiffing: Furry Sexuality

Have you heard of “yiff”, “yiffy”, or “yiffing”? If so, you know that yiff is a cute, versatile euphemism for sex that is popular among furries.

“Yiff” can describe sex between furs, or pornography of it. As a verb, “yiff” means “to have sex” or “to mate”[iv]. Furries may also call someone “yiffy”[v] as a euphemism for “sexy”.

Although “yiff” has nonsexual uses, it’s primarily used to allude to sexuality. The ubiquity of “yiff” in the furry community suggests that furry-themed sexuality is common among furries. Data from furry surveys does, too.

Most people in the furry fandom have sexual interest in furry content[vi]. It’s estimated that about 95% of male furries and almost 80% of female furries look at furry-themed pornography[vii].

Furries are also far more likely to be gay or bisexual than non-furries. One survey found that 30% of male furries and roughly 10% of female furries were mostly or fully homosexual[viii]. In fact, nonheterosexuality is so common among furries that one study of male furries had participants who were more likely to be gay than straight[ix].

Furries are also somewhat likely to report attraction to animals or stuffed animals. One survey of furries found that 17% of them were zoophilic (sexually attracted to animals) and 7% of them were plushophilic (sexually attracted to stuffed animals)[x].

Furries are a marginalized sexual minority[xi], and they often feel that coming out as furry is analogous to disclosing their sexual orientation[xii]. But being part of the furry fandom isn’t just about sex—it’s also about escape, entertainment, community, and a sense of belonging[xiii].

Furry Embodiment as a Form of Autosexuality

In order to better understand male furry sexuality, sexologists Kevin Hsu and J. Michael Bailey surveyed 334 of them about their furry sexual interests[xiv].

Hsu and Bailey proposed the name “anthropomorphozoophilia” for a sexual attraction to anthropomorphic animals, and described a sexual attraction to being one as “autoanthropomorphozoophilia”[xv]. Both of these words are rather long, so I’ll shorten them to “anthrozoophilia” and “autoanthrozoophilia” instead.

If someone is sexually attracted to anthropomorphic animals, they’re anthrozoophilic, and if they’re sexually attracted to being one, they’re autoanthrozoophilic.

A majority of the furries that Hsu and Bailey studied were strongly sexually attracted to anthropomorphic animals as well as the fantasy of being one—approximately 99% were at least a little anthrozoophilic, and more than 90% were at least somewhat autoanthrozoophilic[xvi].

As expected, the gendered component of their anthrozoophilia showed correspondence between internal and external attractions. Furries exclusively interested in female furs tended to be more aroused by imagining themselves as a female fur, and all of the furries exclusively interested in male furs were more aroused by imagining themselves as male furs than female furs[xvii].

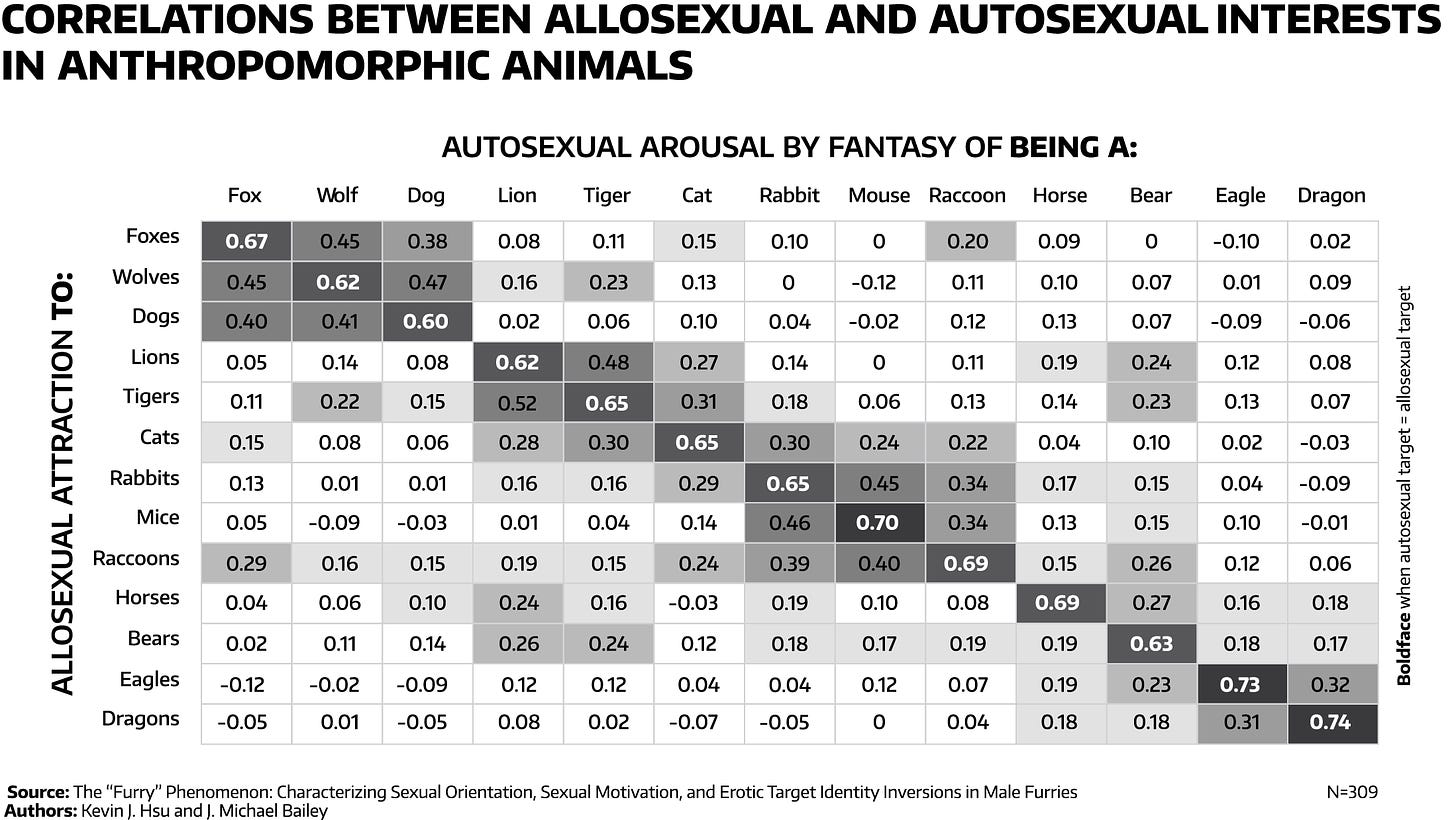

In terms of species, their attractions showed a similar correspondence between autosexual and allosexual attractions. For all thirteen species examined in the study, allosexual attraction to a species of anthropomorphic animal was most strongly correlated with autosexual arousal by the fantasy of being that exact same species.

Hsu and Bailey revealed this congruence between internal and external attractions with a magnificent thirteen-by-thirteen correlation matrix that elegantly demonstrates the relevance of the erotic target identity inversion framework for understanding autosexuality. In this matrix, the next-strongest correlations happened when the different species were similar. Being attracted to felines was associated with being attracted to other types of felines. Attractions to canines showed the same pattern.

I’m a huge fan of Hsu and Bailey’s furry correlation matrix. I’ve included a version of it here so that you can see it in its full glory (see Figure 7.3.1). As with the correlation chart in the prior chapter, correlations of magnitude 0.15 or higher are shaded so that you can better discern the patterns within it.

Altogether, Hsu and Bailey’s findings strongly support the idea that autoanthrozoophilia is a form of autosexuality and anthrozoophilia is its allosexual counterpart.

Later, a group of researchers aligned with the furry fandom conducted a study of furries to see how their results compared to Hsu and Bailey’s[xviii]—at 1,113 responses, their sample was several times larger.

Again, the vast majority of furries said they had sexual attraction to furry media, and most reported moderate to strong amounts of attraction[xix]. Most also reported sexual arousal by the fantasy of being an anthropomorphic animal, showing that anthrozoophilia and autoanthrozoophilia are both common in male furries[xx].

Fursonas: Furry Identity

Through meeting like-minded people and developing an anthropomorphic animal representation of themselves—a fursona[xxi]—furries can explore their identity and express themselves in a supportive, welcoming community.

When picking a species for their fursona, furries are most likely to pick a canine such as a wolf, fox, or dog. Feline species such as lions, tigers, and cats are the second-most popular. Dragons come in third[xxii].

Furries are far more likely than the general population to consider themselves not fully human or to say they would become completely nonhuman if they could[xxiii]. The frequency and intensity of furry role-playing is inversely associated with human embodiment[xxiv], which suggests that when furries yiff as their fursonas, it contributes to feelings of nonhumanity.

Cross-Species Identity and Human Embodiment

To investigate the relationship between someone’s nonhuman identity and their sense of human embodiment, scientists tested how a sample of furries responded to the rubber hand illusion[xxv]. In this experiment, the participant sits with one hand resting on a table while a rubber hand rests where their other hand would if it were on the table. A cloth draped over their shoulder and the base of the rubber hand allows them to more easily imagine that the hand on the table is connected to them.

The real hand and rubber hand are both stroked in the same spots at the same time with a rubber brush. Once the illusion begins, the person sees the rubber hand as part of their own body and may feel as if they could move it if they wanted to. They might also proprioceptively sense that their unused hand has shifted closer to the rubber hand’s location. This phenomenon is known as “proprioceptive drift”. The bigger this shift is, the more they feel a sense of ownership over the rubber hand[xxvi].

Autosexual orientations create attractions to particular states of embodiment. Furries and therians tend to imagine their animal sides with paws, hooves, or wings, not hands.

The dysphoria from shortcomings in the desired type of embodiment can show up as dissociation or alienation from one’s own body, so the rubber hand illusion’s ability to alter a person’s sense of embodiment could let scientists indirectly detect the loss of embodiment associated with species dysphoria and cross-species identity. By testing furries with the rubber hand illusion and using data from a similar study as a control group, scientists were able to measure if being a furry impacted their sense of human embodiment.

It did.

Furries responded less to the rubber hand illusion than the non-furry comparison sample, suggesting that they identified less with the hand. They reported less embodiment and were less likely to feel as if they had lost their hand or that it had disconnected from their nervous system[xxvii].

Furries also experienced less proprioceptive drift than non-furries. This drift was significantly associated with their role-playing habits[xxviii]. The more frequently and intensely they role-played as anthropomorphic animals, the less their real hand felt shifted toward the rubber one, which indicated a lesser degree of human embodiment[xxix].

Less proprioceptive shift was associated with more negative sentiments toward humanity and a stronger mismatch between their identities and bodies[xxx]. The therian subgroup of furries felt an even greater incongruence between their bodies and identities, and also viewed humanity even more negatively than non-therian furries.

Together, these results suggest furry role-playing contributes to a reduced sense of ownership over one’s human body, which itself is associated with negative sentiments toward humanity as well as a greater mismatch between one’s body and identity.

In Sum:

Furries are fans of anthropomorphic animals. Many furries create and develop fursonas representing their anthropomorphic animal selves. Canine, feline, and draconic fursonas are the most common.

Furries commonly wear body adornments such as animal ears or a tail as a way of representing their furry side. The more affluent among them may even own fursuits. It’s common for them to role-play with each other as their fursonas, either in-person or online. Most furries are nonheterosexual.

Furries usually have sexual interest in both anthropomorphic animals and the idea of being one. Among male furries, sexual interest in a particular species of anthropomorphic animal is strongly correlated with autosexual interest in being that same species of anthropomorphic animal.

Furry role-playing is associated with a weaker sense of human embodiment, which itself is associated with negative sentiments towards humanity and greater species incongruence between one’s body and identity.

Speak With Me

Are you an autosexual person who wants to discuss your experiences with someone who actually understands what it’s like? Are you in a relationship with an autosexual person and want to understand them better? Sign up to speak with me! I’m available to speak via Zoom or phone.

[i] “Alt+H FAQ.”

[ii] Roberts et al., “Clinical Interaction with Anthropomorphic Phenomenon,” e48; Roberts et al., “The Anthrozoomorphic Identity,” 535.

[iii] Plante et al., “FurScience! A Summary of Five Years of Research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project,” 112.

[iv] “FGC - A Furry Glossary.”

[v] “The Definition of the Furry Slang Word ‘Yiff’ and How It May Be Used.”

[vi] Evans, “The Furry Sociological Survey,” 8; Plante et al., “FurScience! A Summary of Five Years of Research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project,” 43.

[vii] Plante et al., “FurScience! A Summary of Five Years of Research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project,” 93.

[viii] Plante et al., 84.

[ix] Hsu and Bailey, “The ‘Furry’ Phenomenon,” 8.

[x] Evans, “The Furry Sociological Survey,” 9.

[xi] Roberts et al., “Clinical Interaction with Anthropomorphic Phenomenon,” e46.

[xii] Roberts et al., e48.

[xiii] Plante et al., “FurScience! A Summary of Five Years of Research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project,” 38–42.

[xiv] Hsu and Bailey, “The ‘Furry’ Phenomenon.”

[xv] Hsu and Bailey, 4.

[xvi] Hsu and Bailey, 14.

[xvii] Hsu and Bailey, 15.

[xviii] Brooks et al., “‘Chasing Tail.’”

[xix] Brooks et al., 6.

[xx] Brooks et al., 6.

[xxi] Silverman, “Fursonas,” chap. 3.

[xxii] Plante et al., “FurScience! A Summary of Five Years of Research from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project,” 51.

[xxiii] Plante et al., 78.

[xxiv] Kranjec et al., “Illusory Body Perception and Experience in Furries,” 600.

[xxv] Kranjec et al., “Illusory Body Perception and Experience in Furries.”

[xxvi] Longo et al., “What Is Embodiment?,” 991.

[xxvii] Kranjec et al., “Illusory Body Perception and Experience in Furries,” 599.

[xxviii] Kranjec et al., 600.

[xxix] Kranjec et al., 600.

[xxx] Kranjec et al., 600.