Here, in chapter 2.1 of Autoheterosexual: Attracted to Being the Other Sex, I discuss the autogynephilic wish to have female-typical anatomy.

Bodies are central to sexuality. The types of bodies people are attracted to usually determine their sexual orientation.

Autoheterosexuality follows a similar pattern: autoheterosexuals usually want the same physical traits they find attractive in people of the other sex. This sexual interest in having a female body—anatomic autogynephilia—is likely the most prevalent subtype of autogynephilia[i].

Anatomic AGP commonly includes the desire to have a female face, butt, and vulva as well as breasts. In general, any female traits that autogynephilic people find attractive are traits they would want for themselves.

Maybe they want narrow shoulders, small hands, long legs, small feet, a slender neck, or a big butt. Maybe they wish they were shorter, their jaw was smaller, or their brow ridge jutted out less.

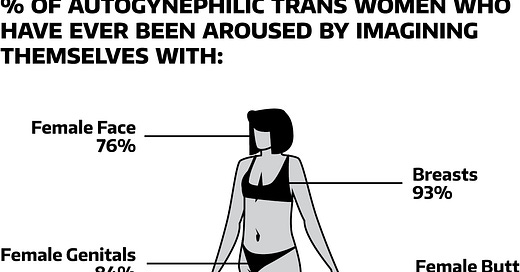

Figure 2.1.1: Prior arousal from anatomic autogynephilia among MTFs

Some autogynephilic people have a strong, selective interest in having a female body and they don’t care about the other feminine stuff. Magnus Hirschfeld described this anatomically-inclined subgroup as “congenitally most strongly predisposed”[ii]. Havelock Ellis said they were “less common but more complete”[iii]. People like this are particularly likely to pursue medical transition.

Effective feminizing technology didn’t exist in Hirschfeld’s time. Fortunately, autogynephilic people today can attain feminine physical traits by taking hormones and having surgeries.

Still, autogynephilic people who are solely interested in having a female body are in a tough position. Unable to find refuge in women’s garb, medical transition is often their best option for satisfying their autogynephilic desires.

Anatomic Autogynephilia before Transsexualism

Autogynephilic people are more likely to want female breasts than any other body part[iv].

Firsthand narratives from the early 1900s frequently report the desire for breasts[v]. The mammary yearning was real: “I want real breasts very badly indeed”[vi], said one transfem.

Transfems whose anatomic interests were strong and persistent were especially likely to experience phantom shifts and feel that they were growing breasts, that their genitals became a vulva, or that they had long hair when their hair was actually short[vii].

One of the transfems Ellis profiled suffered from genital dysphoria and only refrained from castrating themselves because of the danger of doing so. “I know that I should be immensely happier if my sexual organs were removed”[viii], she said. After her wife’s death, another transfem made a habit of sleeping with her genitals tucked between her legs, out of view[ix].

One of the transfems in Hirschfield’s book memorably reported, “There is something beastly in the boastful exhibition of the male organ”[x].

In these narratives, desire for female anatomy could extend to any physical feature and even to the body as a whole. This desire to see themselves as feminine also shifted their self-perception in that direction[xi].

One transfem perceived that her hips were wide like female hips, although in reality, they were only slightly wider than average male hips[xii]. Another transfem derived pleasure from perceiving that her small hands and feet were womanly[xiii].

Another transfem grew excited by her growing corpulence, which she considered to be the “formation of the flesh of the woman”[xiv]. At age thirty-seven, a transfem reported that her body was becoming more feminine over time[xv].

Fueled by a persistent desire to make their bodies more feminine, some transfems used various herbs, oils, or medical salves with the hope of becoming physically feminized[xvi]. One transfem ordered a product advertised to improve breast size, but it didn’t work[xvii]. Another massaged her breasts with olive oil, hoping it would increase their size[xviii].

Unfortunately, none of these approaches worked. Effective feminizing technology didn’t exist yet.

Anatomic Autogynephilia in the Age of Transsexualism

Once medical technology made hormones and surgeries available, it became possible for more trans people to achieve a cross-gender aesthetic that allowed them to exist in society as their cross-gender self.

Even though this medical technology wasn’t nearly as refined as it is today, the advent of transsexualism represented a massive breakthrough for trans people.

The situation is even better now: it’s easy to obtain hormones over the internet, and it’s becoming easier to get them in person, too. As society becomes more aware and accepting of trans people, more medical establishments are offering hormone prescriptions on an informed-consent basis.

These cross-sex hormones help trans people attain hormone levels more like those of the other sex, which helps them more closely resemble the other sex.

Most trans people refer to these hormones as hormone replacement therapy. They have come up with many creative, punny names for these hormones:

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has many nicknames among transfeminine people, including titty pills, titty skittles, smartitties, chicklets, anticistamines, mammary mints, life savers, tit tacs, breast mints, femme&m’s, antiboyotics, trans-mission fluid, and the Notorious H.R.T.[xix]

Notice a theme? About half of these names allude to female breasts. Having breasts is critically important to many transfems.

It’s common for transfems to wear silicone breast forms to temporarily attain a full-chested look. They may also wear a padded bra or choose to stuff a bra. If they don’t achieve sufficient breast growth after being on hormones for a few years, they may decide to get breast augmentation surgery.

Transfems who want a vulva may seek vaginoplasty (the surgical creation of a neovagina), commonly called “bottom surgery”. Over the years, this surgical procedure has also been called “sexual reassignment surgery”, “gender reassignment surgery”, or “gender confirmation surgery”.

To achieve a more feminine facial structure, some transfems undergo a series of surgical procedures collectively referred to as facial feminization surgery (FFS). This commonly includes procedures like forehead contouring, jaw contouring, and rhinoplasty (nose job).

Humans usually identify each other by facial recognition, so facial structure is a big part of identity. If part of the face is covered up, we may not recognize someone we already know. When seeing other people’s faces, it only takes a fraction of a second to attribute a gender to them[xx], which makes FFS a particularly important intervention for transfems who have issues with people gendering them appropriately in everyday life.

Although other procedures exist beyond the ones mentioned here, transsexual women tend to be most consistently interested in surgical interventions in three key areas: face, chest, and genitals.

All these areas have great symbolic value for signifying gender. They are also attractive: gynephilic people are usually attracted to feminine faces, vulvas, and breasts, so autogynephilic people often want those same features for themselves.

In Sum:

Anatomic autogynephilia often makes autogynephilic people want the same feminine physical features they find attractive in others. They may want a female face, butt, or vulva; breasts; or anything else they deem female-typical. Unsurprisingly, breasts are the single most desired female physical feature.

Before transsexualism existed, many autogynephilic transfems longed for feminine anatomy in vain because the technology didn’t exist yet. But once surgeries and pharmaceutical hormones were developed, a few of them had a chance to more closely resemble the other sex with the help of these technologies.

Today, many autogynephilic people have access to gender-affirming medical care that previous generations couldn’t get. These feminizing hormones and surgeries not only help them feel more comfortable with themselves but also increase the odds that other people will regard them as women.

Speak With Me

Are you an autosexual person who wants to discuss your experiences with someone who actually understands what it’s like? Are you in a relationship with an autosexual person and want to understand them better? Sign up to speak with me! I’m available to speak via Zoom or phone.

[i] Hsu, Rosenthal, and Bailey, “The Psychometric Structure of Items Assessing Autogynephilia,” 11–12.

[ii] Hirschfeld, Transvestites, 183.

[iii] Ellis, “Eonism,” 36.

[iv] Blanchard, “Partial versus Complete Autogynephilia and Gender Dysphoria,” 304; Hsu, Rosenthal, and Bailey, “The Psychometric Structure of Items Assessing Autogynephilia,” 7.

[v] Ellis, “Eonism,” 51,82,98; Hirschfeld, Transvestites, 120.

[vi] Ellis, “Eonism,” 49.

[vii] Hirschfeld, Transvestites, 183.

[viii] Ellis, “Eonism,” 66.

[ix] Ellis, 94.

[x] Hirschfeld, Transvestites, 122.

[xi] Hirschfeld, 129.

[xii] Hirschfeld, 73.

[xiii] Ellis, “Eonism,” 50.

[xiv] Hirschfeld, Transvestites, 57.

[xv] Hirschfeld, 62.

[xvi] Hirschfeld, Sexual Anomalies and Perversions, 200.

[xvii] Ellis, “Eonism,” 49.

[xviii] Ellis, 82.

[xix] Ashley, “Surgical Informed Consent and Recognizing a Perioperative Duty to Disclose in Transgender Health Care,” 75.

[xx] Dobs et al., “How Face Perception Unfolds over Time,” 4.