Taking into account both sexes and both known transgender etiologies, there are four distinct groups of transgender people. Using data on their reported sexual orientations, it’s possible to estimate the relative prevalence of each group with the two-type typology.

Recall that the two-type typology sorts trans people based on their sexual orientation with respect to their birth sex. If they’re strictly homosexual, they go into the homosexual category. If they’re nonhomosexual (heterosexual, bisexual, or asexual), they go into the autoheterosexual category.

Since some autohets do have same-sex partner preferences, estimates that rely on the two-type typology will underestimate the true prevalence of autoheterosexual transgenderism, but they’re a good start.

Before I present etiology prevalence estimates that categorize the transgender community into its four main groups, I want to illustrate some of the fuzziness inherent to this effort to make clear these are estimates, not exact figures.

Many factors affect the sort of data transgender researchers receive. Depending on whom they talk to and the sorts of questions they ask, they get different answers.

Measuring Sexual Orientation: Identities and Attractions

Depending on how people are asked about their sexual orientation, they give different responses. For instance, the sexual identities they report don’t always match their attractions, fantasies, or behavior.

The gender-flipping nature of transition makes things even more confusing. The meaning of identities associated with homosexuality and heterosexuality become ambiguous: If a trans person says they’re heterosexual, is that with respect to their gender identity or their sex?

Asking about sexual identity on its own is probably the worst way to get accurate information on people’s sexual orientations—it’s also important to ask about their attractions, behavior, or fantasies. Imagination is the only limit when it comes to sexual fantasy, and sexual orientation is commonly defined based on attraction, so it’s smart to ask study participants about attractions and fantasies.

Although there are many ways to ask about sexual orientation, most measures get in the same general ballpark. What matters is that it’s measured, and getting a few measures is better than just one.

The Impact of Time, Space, and Culture on Estimates of Trans Etiology

The way in which transgenderism researchers find their study participants affects the relative proportions of homosexuals and nonhomosexuals in their samples. Internet-based studies[i] tend to find more nonhomosexual trans people than studies from gender clinics[ii].

There’s also the issue of timing: is the study surveying pre- or post-transition trans people? As seen in the prior chapter, the sexual orientations that trans people report often change based on where they are in their gender trajectory.

Timing also matters on a societal level. In recent years, there has been a major shift in the types of people seeking gender-affirming medical care. Adolescent referrals to gender clinics have become female-dominant[iii]. People with nonhomosexual orientations are showing up more often, too[iv].

These changes over the past few decades demonstrate that culture impacts the proportion of trans people who fall into each of the four groups.

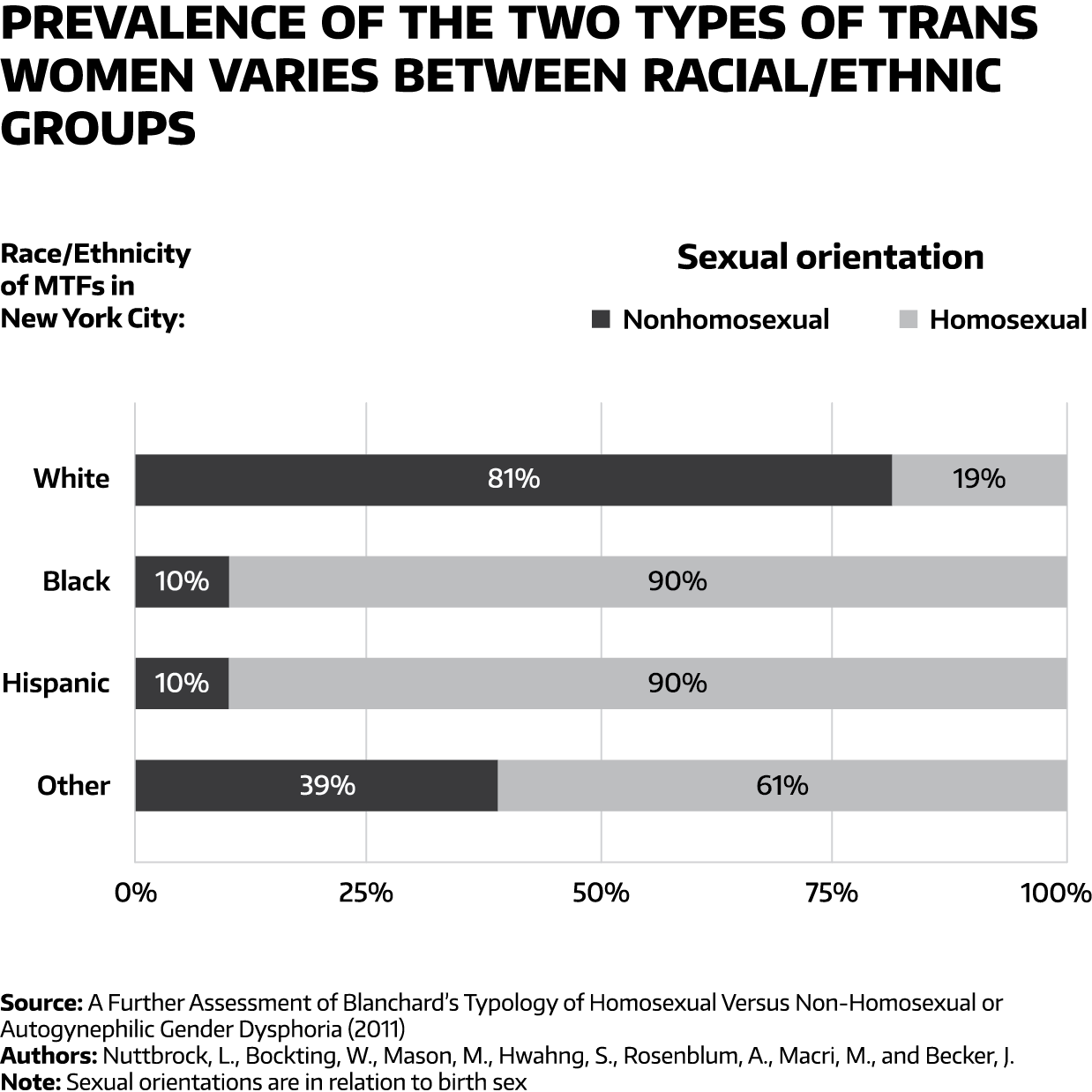

For example, race and ethnicity impact the proportion of trans women who belong to either etiology. In the large study of trans women in the New York City metropolitan area that replicated Blanchard’s first typology study, researchers found drastic differences based on race and ethnicity: 90% of the hispanic and black trans women were homosexual[v], but only 19% of the white trans women were homosexual (see Figure 5.3.1).

If these patterns hold for other places in the US, then among Americans, white trans women are usually autoheterosexual and black or hispanic trans women are usually homosexual.

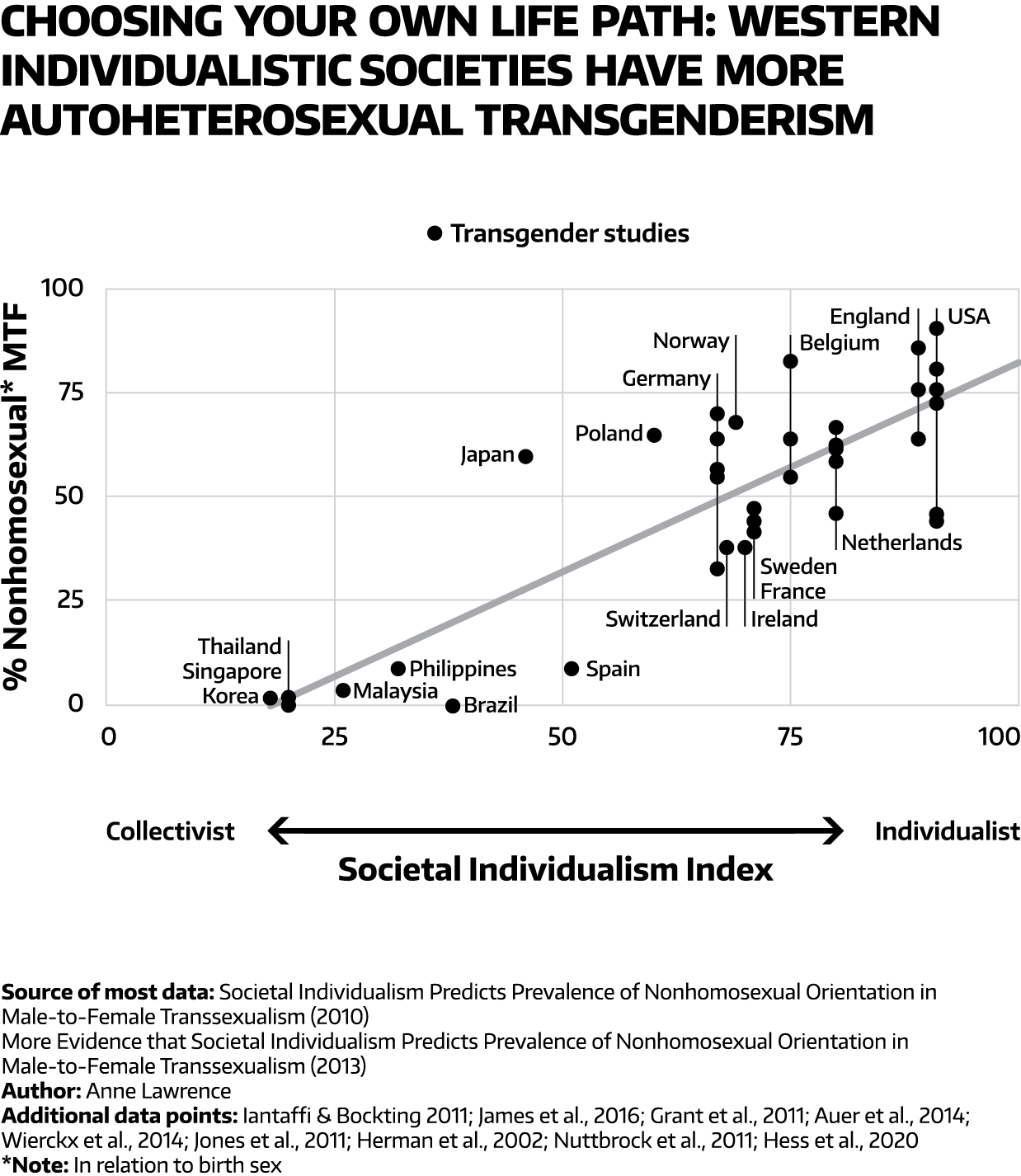

I suspect that culture impacts this difference more than genes, because culture strongly influences etiology ratios among trans women. In particular, the degree to which a society is individualistic or collectivistic (“I” vs. “we”) strongly predicts the proportion of trans women who come from either etiology[vi].

Anne Lawrence figured this out. In her model, about three-fourths of nonhomosexual MTF prevalence was predicted by societal individualism[vii]. Individualistic countries clearly had the most nonhomosexual MTFs, while collectivistic countries had the least (see Figure 5.3.2)[viii].

This difference in societal organization makes a massive impact: it’s apparently far more feasible in Western, individualistic countries for autohet MTFs to live as women.

As a freedom-lover, I like what this finding implies: the relative prevalence of autoheterosexual transgenderism is an indirect indicator of how free we are to live in alignment with our strongly held feelings.

When we see autohet trans people where we live, it’s a sign that we are free to live in the way that suits us.

Transgender Americans are Usually Autohet

Hopefully it’s clear by now that estimates of trans people’s sexual orientation vary depending on their race or ethnicity, their stage of transition, the degree of individualism in their cultural milieu, and whether their answers have potential consequences for receiving medical care (gender clinic vs. online).

There are undoubtedly other factors as well, and there is an inherent fuzziness to figuring out this ratio that we can’t fully eliminate. Still, I anticipate some readers will want to know some numbers they can cite as a reasonable statistic when talking about transgenderism.

For that, I’ll reference two enormous surveys of Americans: the 2011 National Transgender Discrimination Survey (2011 NTDS)[ix] and the 2015 United States Transgender Survey (2015 USTS)[x].

All the trans people who took these surveys were from the US, and a little over 80% of them were white. Except for the 7% of respondents in the 2011 NTDS who filled out their survey in-person[xi], everyone took these surveys over the internet.

Almost 80% of those who filled out the 2011 NTDS in-person were not white, while those who took it online were 80% white[xii]. This suggests that online surveys will underestimate the true prevalence of trans people who aren’t white—and since nonwhite trans people are more likely to be of homosexual etiology than white trans people, online surveys will likely underestimate the true prevalence of homosexual transgenderism.

These three factors—white race, individualistic culture, and online survey—are all associated with higher estimates of nonhomosexuality, and therefore higher estimates of autoheterosexuality.

Despite these limitations, I chose these data sources for a few reasons:

They had massive samples

They weren’t administered in a medical setting, so the trans people taking them knew their answers couldn’t be used to withhold medical care

Dozens of researchers have used these two datasets to publish studies of their own, which implies that many researchers consider them worthwhile

The 2011 NTDS and 2015 USTS asked about sexual orientation in terms of sexual identity as bisexual, queer, asexual, gay/lesbian/same-gender-loving, straight/heterosexual, or other/not listed. The 2015 USTS also had a pansexual category.

In line with contemporary transgender social norms, I interpreted “straight” and “heterosexual” responses in relation to gender identity, which placed them in the homosexual etiology. I sorted “gay/lesbian/same-gender-loving” responses into the nonhomosexual etiology by this same logic.

I interpreted “pansexual” as a synonym for “bisexual” and categorized both as nonhomosexual. Asexuals went into the nonhomosexual category as well.

“Queer” is ambiguous by design and its meaning can be hard to pin down, but it’s just another way of saying nonalloheterosexual. A previous study showed that almost three-quarters of queer-identified trans men in their sample had nonhomosexual attractions[xiii], so I sorted queer trans men accordingly. I lacked a comparable reference for sorting the 6–7% of trans women who identified as queer, so I put them all into the nonhomosexual category.

I placed trans people who selected “other/not listed” as their sexual orientation in the nonhomosexual category—I figured if their sexual identity was too unique to pick “heterosexual” or “straight”, they were probably nonhomosexual.

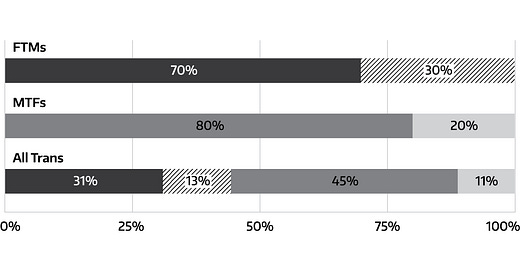

Based on this typology-based sorting, autoheterosexuals are by far the most prevalent etiology among transgender Americans. About 70% of trans men and 80% of trans women in America are of autoheterosexual etiology.

Overall, autogynephilic MTFs are the most common type of transgender American. Autoandrophilic FTMs are the second-most common. Homosexual MTFs and FTMs each represent about an eighth of the overall total.

Approximately three-quarters of transgender Americans are of autoheterosexual etiology. The rest are of homosexual etiology.

Chapter 5.3 Recap:

The two-type typology sorts trans people into different etiologies based on their sexual orientation. Homosexual trans people are sorted into the homosexual etiology, while nonhomosexual trans people are sorted into the autoheterosexual etiology. Given that there are two known transgender etiologies in each sex, it’s possible to sort trans people into four distinct groups based on their reported sexual orientations and thus determine the relative prevalence of each group.

Study methodologies affect these estimates of etiology ratios. Researchers usually arrive at different estimates for the sexual orientations of trans people based on whether they ask about sexual identities, attractions, behaviors, or fantasies. The way they find trans participants makes a difference, too: internet-based studies tend to have a higher ratio of nonhomosexual trans people than gender-clinic-based studies. Whether study participants are pre- or post-transition matters, as does whether or not it’s a recent study.

Culture strongly influences the relative prevalence of homosexual and autoheterosexual trans people. Homosexual transgenderism is more common in collectivistic societies, and autoheterosexual transgenderism is more common in individualistic societies. Another sign of culture’s influence is the drastically different etiology prevalence ratios among trans women based on their racial or ethnic group. Data from New York City suggests that in the US, black or hispanic trans women are usually of homosexual etiology, while white trans women are usually of autoheterosexual etiology.

Applying the two-type typology to the largest surveys of transgender Americans yields an estimate that approximately 70% of trans men and 80% of trans women are autoheterosexual. In America, autohet trans people are approximately three times as common as homosexual trans people.

Speak With Me

Are you an autosexual person who wants to discuss your experiences with someone who actually understands what it’s like? Are you in a relationship with an autosexual person and want to understand them better?

[i] Iantaffi and Bockting, “Views from Both Sides of the Bridge?”; Grant et al., “Injustice At Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey”; James et al., “The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey.”

[ii] Defreyne et al., “Sexual Orientation in Transgender Individuals,” November 2021; Auer et al., “Transgender Transitioning and Change of Self-Reported Sexual Orientation”; Smith et al., “Transsexual Subtypes”; Wierckx et al., “Sexual Desire in Trans Persons”; Jones et al., “Brief Report”; Lawrence and Bailey, “Transsexual Groups in Veale et al. (2008) Are ‘Autogynephilic’ and ‘Even More Autogynephilic.’”

[iii] Zucker and Aitken, “Sex Ratio of Transgender Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis.”

[iv] Aitken et al., “Evidence for an Altered Sex Ratio in Clinic‐Referred Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria.”

[v] Nuttbrock et al., “A Further Assessment of Blanchard’s Typology of Homosexual Versus Non-Homosexual or Autogynephilic Gender Dysphoria,” 253.

[vi] Lawrence, “Societal Individualism Predicts Prevalence of Nonhomosexual Orientation in Male-to-Female Transsexualism”; Lawrence, “More Evidence That Societal Individualism Predicts Prevalence of Nonhomosexual Orientation in Male-to-Female Transsexualism.”

[vii] Lawrence, “Societal Individualism Predicts Prevalence of Nonhomosexual Orientation in Male-to-Female Transsexualism,” 573.

[viii] Lawrence, “Societal Individualism Predicts Prevalence of Nonhomosexual Orientation in Male-to-Female Transsexualism”; Lawrence, “More Evidence That Societal Individualism Predicts Prevalence of Nonhomosexual Orientation in Male-to-Female Transsexualism”; Iantaffi and Bockting, “Views from Both Sides of the Bridge?”; James et al., “The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey”; Grant et al., “Injustice At Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey”; Auer et al., “Transgender Transitioning and Change of Self-Reported Sexual Orientation”; Wierckx et al., “Sexual Desire in Trans Persons”; Jones et al., “Brief Report”; Herman-Jeglińska, Grabowska, and Dulko, “Masculinity, Femininity, and Transsexualism”; Nuttbrock et al., “A Further Assessment of Blanchard’s Typology of Homosexual Versus Non-Homosexual or Autogynephilic Gender Dysphoria”; Hess et al., “Change in Sexual Attraction and Sexual Partnership Within the Individual Transition Process in Transwomen.”

[ix] Grant et al., “Injustice At Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey.”

[x] James et al., “The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey.”

[xi] Reisner et al., “Comparing In-Person and Online Survey Respondents in the U.S. National Transgender Discrimination Survey,” 101.

[xii] Reisner et al., 102.

[xiii] Meier et al., “Measures of Clinical Health among Female-to-Male Transgender Persons as a Function of Sexual Orientation,” 468.