This is Chapter 7.0 of Autoheterosexual: Attracted to Being the Other Sex, a book about the orientation behind most instances of gender transition in Western, individualistic countries. This short chapter quickly describes the general form of autosexual orientations and their respective forms of trans identity, along with my rationale for writing chapters on all these forms of trans identity.

Heterosexuality isn’t the only sexual orientation that can be turned inside out.

It happens with age-based or race-based attractions too. Even attractions to nonhuman entities such as dragons and wolves can be inverted, resulting in a sexual desire to be a dragon or wolf.

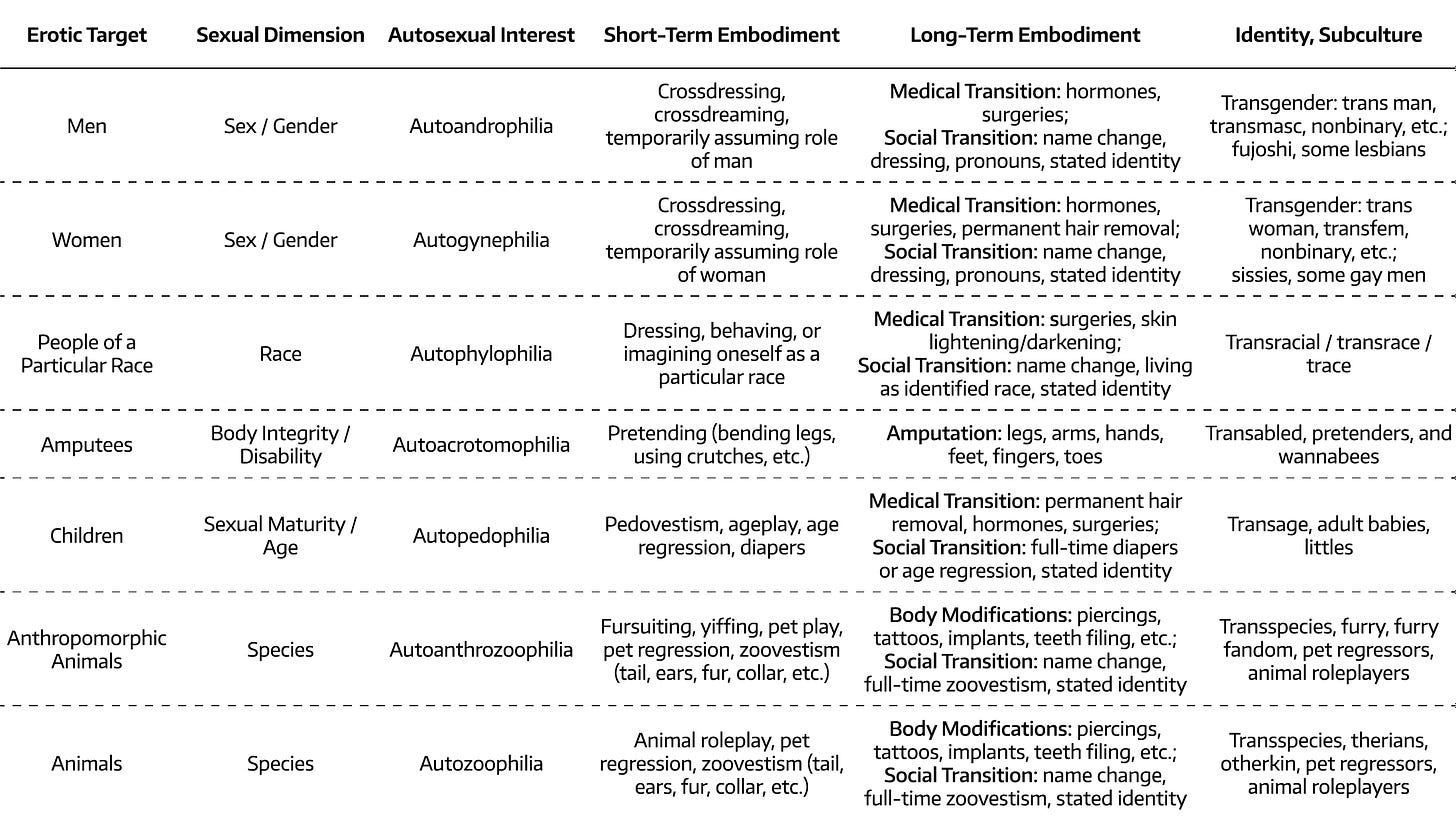

What do all these different autosexual orientations have in common?

Each one is theorized to be an erotic target identity inversion (ETII).

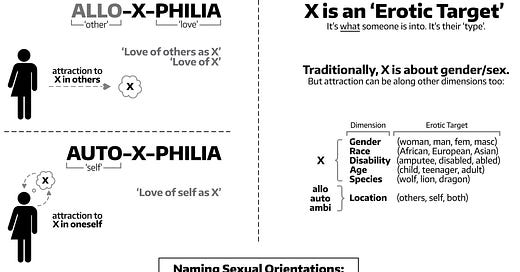

When it comes to ETIIs, the particular erotic target may vary in gender, race, body integrity, age, or species (i.e., between men, women, amputees, youth, wolves, etc.), but the direction of the attraction is the same: inverted toward the self.

Erotic target identity inversions are self-attractions (autophilias), so the names for these orientations take the form of “auto-X-philia”, where X is the erotic target being embodied. For example, an inverted attraction to men is autoandrophilia, and an inverted attraction to animals is autozoophilia.

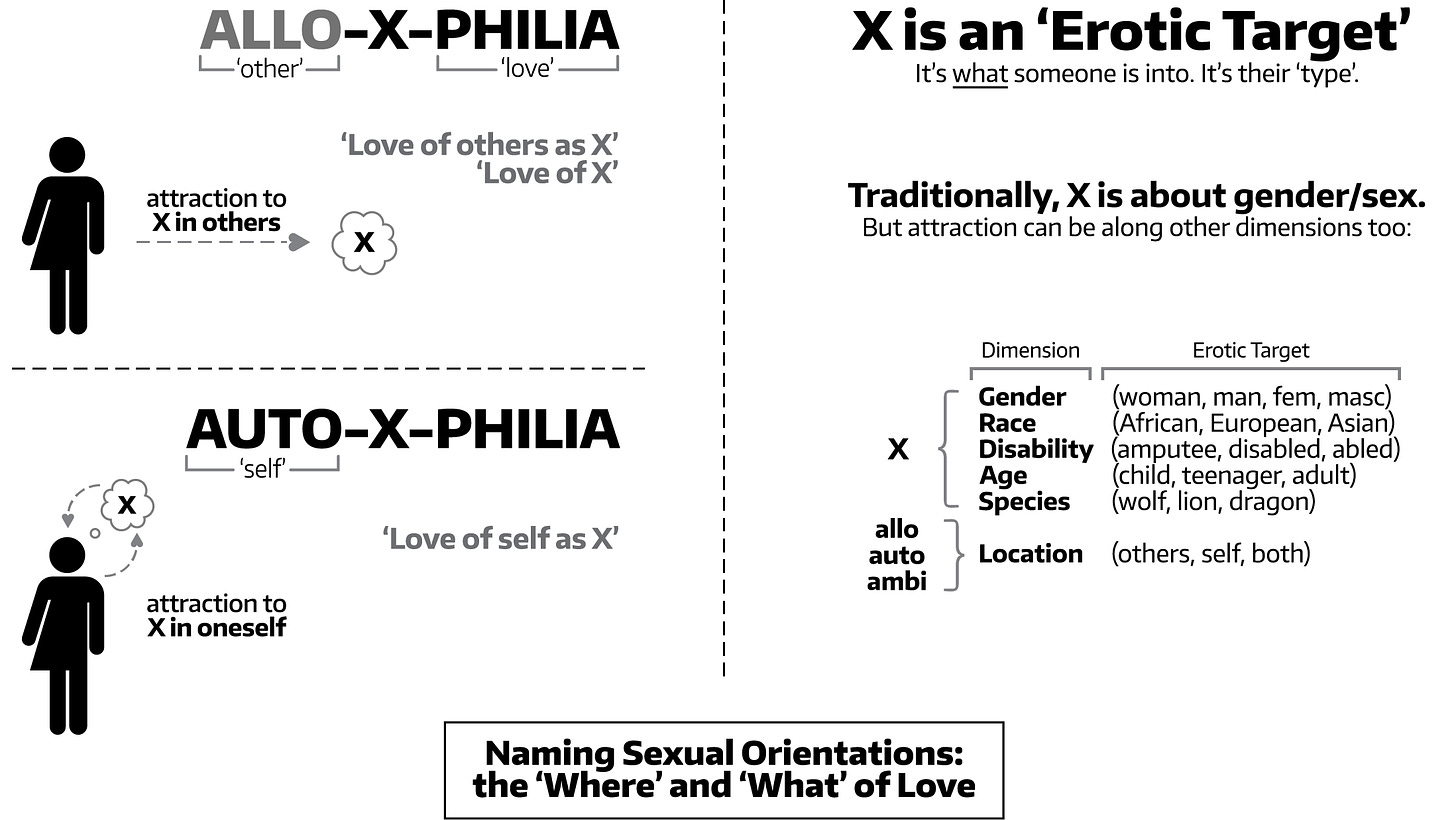

All of these autosexual orientations have the potential to shift someone’s identity closer to that of their erotic target. Just as autoheterosexuality can lead a person to identify as another gender, autosexual attraction to being an amputee can motivate someone to identify as an amputee.

Any of these autosexual orientations can cause shifts toward mentally or physically feeling like the erotic target. During mental shifts, autosexuals feel they are having thoughts, feelings, perceptions, or sensations corresponding to their erotic target. During phantom shifts, autosexuals feel the presence of phantom anatomy corresponding to their erotic target.

People with autosexual orientations often want to embody the same traits they admire in the entities they’re attracted to. Different types of entities vary with respect to their physical form, bodily functions, mind, behavior, dress, or social role. Thus, people with autosexual orientations can have sexual or romantic interests that fall within one or more of the following embodiment categories:

Anatomic autosexuality—having the physical traits of an erotic target

Physiologic autosexuality—having the bodily functions of an erotic target

Behavioral autosexuality—behaving as an erotic target

Sartorial autosexuality—wearing clothing or other body adornments associated with an erotic target

Interpersonal autosexuality—being socially treated as an erotic target

Psyche autosexuality—having the consciousness of an erotic target

Regardless of which type of autosexual orientation someone has, emotional suffering sometimes accompanies it. As cross-identity strengthens through reinforcement, autosexuals can feel dissatisfaction and unhappiness from the mismatch between their idealized self-image and their physical form.

The specific type of autosexual dysphoria depends on the type of entity that they want to embody. For example, if someone experiences negative emotions because of their unmet wish to be a dragon or a wolf, they have species dysphoria.

Autosexual dysphoria can be described even more specifically based on the specific aspects of the erotic target that an autosexual person wants to embody. For example, if someone is dysphoric because of their unmet wish to have fur, paws, and a tail, they have anatomic species dysphoria.

Autosexuals who are dysphoric about their embodiment may wonder if they would be better off living as their erotic target, or if they should get surgeries or body modifications to more fully embody it. But before getting surgeries or making other permanent changes, autosexuals usually embody their erotic target temporarily through clothing or other body adornments, behavior, roleplay, or mental shifts. This temporary embodiment brings comfort, arousal, or a sense of identity and is an important part of the cross-identity development process.

There are particular details unique to each type of autosexual orientation and each individual who has one, but this is the general form that autosexual orientations take.

In brief, this is the autosexual theory of trans identity: for each attraction to, there exists a corresponding attraction to being, and for each attraction to being, there exists a corresponding type of trans identity—each with its own flavor of embodiment subtypes, euphoria/dysphoria, and shifts.

Variations in Erotic Target Location

Most people are attracted to other people: the location of their attraction is on others—they’re allosexual.

When the location of attraction ends up elsewhere, however, it’s theorized to be a form of erotic target location error (ETLE). It’s called this because it’s a variation in “where” instead of “what”[i]. The type of erotic target is the same (woman, man, amputee, etc.), but the location is different (self versus others)[ii].

The “error” part of the name comes from the evolutionary logic that alloheterosexuality is the optimal orientation for sexual reproduction, so other types of orientations can be considered errors of sexual development to some degree.

As originally envisioned[iii], the ETLE concept supposedly accounts for sexual fetishism, transvestism, and autoheterosexuality. Ray Blanchard developed the theory after he found that many gender-dysphoric patients who had been aroused by imagining themselves as the other sex had also been aroused by dressing as the other sex or by certain materials or garments[iv].

In this etiological theory, when an erotic target location gets placed on clothing or textiles rather than the body beneath them, it can result in sexual fetishism (attraction to nonliving objects such as clothing, shoes, or materials). When attraction to a clothed person of the other sex gets placed on the self, it results in transvestism. And when attraction to bodies of the other sex gets placed on the self, it leads to autoheterosexuality[v].

Although it’s a promising explanation for the origin of autosexual orientations, these orientations clearly exist whether or not the ETLE theory ends up holding true. ETLE is simply the current leading theoretical explanation for what causes them.

Why Have Chapters on Other Autosexual Orientations?

Learning about other autosexual orientations creates a deeper, more nuanced picture of autosexuality, but that’s not the primary reason why I’ve included these autosexuality chapters. They’re here to strengthen the case for autoheterosexuality and its relevance to transgenderism.

There are plenty of essays[vi], videos[vii], and blog posts[viii] claiming that autoheterosexuality and the two-type model are not just incorrect but are also harmful, pathologizing, and transphobic. These critiques are very popular among those of my kind who reject the sexuality-based explanation for their situation. Explaining all the little details about how these critiques are mistaken would bore the shit out of too many readers, so I will bypass these critiques instead of addressing them directly.

I’ve composed chapters on other autosexual orientations and their corresponding trans identities that are based on disability (7.1), age (7.2), species (7.3–7.5), and race (7.6). Acknowledging that even one of these forms of trans identity exists makes the existence of autoheterosexuality and autohet transgenderism seem not only possible, but inevitable.

For example, consider the case of draconic identity.

When asked, people who identify as dragons are likely to report sexual interest in dragons as well as sexual interest in being a dragon. Is a dragon identity best explained by saying everyone has a species identity and people who identify as human are cis-species, but sometimes for unknown (and definitely nonsexual) reasons, people end up with a transspecies identity? Or does it make more sense to recognize that autosexual attraction to being a dragon can drive the development of a dragon identity?

I think the latter scenario makes sense not just for draconic identities, but for autosexual trans identities in general. My hope is that readers will see it similarly.

If you’re reading this book strictly to learn about autoheterosexuality and aren’t interested in learning about other types of autosexual trans identity, you may want to skip ahead to Part 8.

Each autosexual orientation has some language specific to it, and the subcultures associated with each orientation have developed their own way of speaking about their experiences, so you also might want to skip ahead if you’ve already hit your quota of new vocabulary.

But I hope you’ll decide not to skip these chapters. Understanding how autosexuality manifests in other types of attractions will give you a deeper understanding of autoheterosexuality than you can get just by learning about autoheterosexuality itself.

In Sum

Autosexual orientations are attractions to being a particular type of entity. Autosexuals are usually allosexually attracted to the same types of entities they wish to embody.

Erotic target location error (ETLE) theory proposes that location is an aspect of sexual orientation and that autosexual orientations come about when the location is one’s own body rather than the bodies of others. It’s a difference in “where”, not “what”. Autosexual orientations are like allosexual orientations except for their inverted directionality, so they are formally known as erotic target identity inversions (ETIIs).

Autosexual orientations compel people to attain particular forms of embodiment, and they foster attachments to that embodiment over time, thus strengthening feelings of cross-identity. Autosexuals can feel dysphoria in response to perceived shortcomings of cross-embodiment and euphoria in response to perceived attainment of cross-embodiment. The specific types of euphoria, dysphoria, and cross-identity that an autosexual person experiences depend on which dimensions of attraction are part of their autosexuality and which aspects of their erotic target they wish to embody.

Many autosexuals temporarily embody their erotic target through body adornments, behavior, fantasies, roleplay, or shifts. Some may take drugs, have surgeries, or get body modifications to permanently attain a higher degree of cross-embodiment and more fully become what they love.

Speak With Me

Are you an autosexual person who wants to discuss your experiences with someone who actually understands what it’s like? Are you in a relationship with an autosexual person and want to understand them better?

[i] Kurt Freund and Ray Blanchard, “Erotic Target Location Errors in Male Gender Dysphorics, Paedophiles, and Fetishists,” British Journal of Psychiatry 162, no. 4 (April 1993): 562, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.162.4.558.

[ii] Anne A. Lawrence, “Clinical and Theoretical Parallels Between Desire for Limb Amputation and Gender Identity Disorder,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 35, no. 3 (June 2006): 263–78, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9026-6.

[iii] Ray Blanchard, “Clinical Observations and Systematic Studies of Autogynephilia,” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 17, no. 4 (1991): 246–48, https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239108404348.

[iv] Blanchard, 244.

[v] Blanchard, 246–47.

[vi] Julia M. Serano, “The Case Against Autogynephilia,” International Journal of Transgenderism 12, no. 3 (2010): 176–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2010.514223; Julia Serano, “Autogynephilia: A Scientific Review, Feminist Analysis, and Alternative ‘Embodiment Fantasies’ Model,” The Sociological Review 68, no. 4 (2020): 763–78, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120934690.

[vii] “Autogynephilia,” ContraPoints, February 1, 2018, YouTube video, 48:54,.

[viii] Jack Molay, “All You Need to Know about ‘Autogynephilia,’” Crossdreamers (blog), July 5, 2014, https://www.crossdreamers.com/2014/07/the-autogynephilia-theory-again.html.