Categorizing effeminate males into two types is nothing new.

Centuries before Western scientists began to study homosexuality and transvestism, Islamic legal scholars wrote about effeminate males known as mukhannathun, which roughly translates to “effeminate ones” or “ones who resemble women”.

These scholars were trying to prescribe social rules rather than understand gender or sexuality, but the two types of mukhannathun they described closely resemble the two types of MTFs we know exist today.

The mukhannathun didn’t fit neatly into either gender role, so legal scholars discussed how—and if—they ought to be incorporated into society.

Writing in the eleventh century AD, a scholar named al-Sarakhsi differentiated between two types of mukhannathun when addressing the question of whether they ought to be allowed in a harem, the part of the house where women dwelled. One type of mukhannathun could be permitted entry, but the other:

“In evil acts is, like other men—indeed, like other sinners—prohibited from women; as for the one whose limbs are languid and whose tongue has a lisp by way of natural constitution, and who has no desire for women and is not mukhannath in evil acts, some of our shaykhs would grant such a person license to be with women.”[i] [Some Arabic words removed for clarity]

The naturally effeminate type who was not interested in women had permission to enter a harem, but the type that was attracted to women was barred.

A few hundred years later, a scholar named al-Kirmani also wrote about mukhannathun. He defined them as men who imitate women in speech and behavior, and he differentiated between two types of male effeminacy: constitutional and affected[ii]. Later writers also distinguished between intentional and unintentional effeminacy, suggesting that this difference was a recurring pattern across generations.

Taken together, these observations suggest that the scholars were aware of two different kinds of effeminate males:

Those who innately spoke and moved like women, yet had no desire for them

Those who could be attracted to women and whose feminine behavior seemed intentional

Although there’s no way to know for sure whether they were describing the same two types we know of today, the resemblance is obvious.

Hirschfeld’s Transvestite Taxonomy

Until Magnus Hirschfeld published Die Transvestiten in 1910, scientists usually saw male femininity as a sign of homosexuality. But after Hirschfeld conclusively demonstrated that male transvestites were usually attracted to women and driven by a love of female beauty, it was clear that transvestism was distinct from homosexuality.

This finding ultimately led to a new question: how many types of transvestites are there?

Hirschfeld classified them into four categories based on sexual orientation—homosexual, heterosexual, and bisexual groups based on attraction to men, women, or both, plus a fourth group that was either asexual or automonosexual (attracted to themselves and no one else)[iii].

Unfortunately, Hirschfeld’s sexual research and political activism for the liberation of sexual minorities encountered changing political tides. In 1920, he was brutally assaulted[iv]. In 1933, Nazis ransacked his sexual institute, burned all the books and case notes in a giant bonfire, and likely killed the sexual minorities they found inside.

After Nazis suppressed Hirschfeld’s work, decades passed before scientists dove back into the search for a reliable classification system for trans people.

Differentiating Transsexuals from Homosexuals and Transvestites

Following Hirschfeld, the next serious attempt at categorizing trans people appeared in Harry Benjamin’s The Transsexual Phenomenon[v], the first book about transsexualism to reach a wide audience.

Benjamin’s taxonomy, the Sex Orientation Scale, placed MTFs on a six-point scale ranging from pseudo-transvestite all the way to true transsexual. Half the categories described different types of transvestites, and the other half described different types of transsexuals.

His scale was intended to categorize MTFs based on medical necessity, not etiology. Its purpose was to help determine whether they would be good candidates for hormones or vaginoplasty; it didn’t categorize based on discrete developmental pathways.

Unfortunately, to qualify as a “true transsexual” on the scale, a patient had to be mostly attracted to men. This contributed to a tradition of gatekeeping MTFs who preferred women—a pattern that continued for decades afterward. In fact, this type of gatekeeping still happens sometimes when clinicians aren’t hip to the two-type model.

This gatekeeping incentivized trans women to portray themselves in whatever way would allow them to have the surgeries they wanted. In order to get the medical care that could ease their suffering, they had to fit the transsexual category as described in the academic literature.

Addressing Suffering: Gender Dysphoria Syndrome

In 1974, Norman Fisk introduced the concept of gender dysphoria syndrome in an influential paper[vi] that shifted the focus toward alleviating suffering rather than deciding if patients were “true transsexuals”.

After seeing that patients had strikingly similar stories, Fisk felt that many MTF gender patients had read the scientific literature on transsexualism and portrayed themselves as textbook cases in order to get the surgeries they needed.

Many of those patients were satisfied with the results of the surgeries, so he concluded that it was more pragmatic for clinicians to focus on improving a patient’s quality of life rather than trying to determine whether they fit the transsexual mold. He saw that transsexuals were “in full flight from either effeminate homosexuality or transvestitism”[vii] and that they sought a transsexualism diagnosis for valid reasons.

Treating gender-related suffering directly instead of trying to decide if any given patient was “actually transsexual” was a big deal. This shift in perspective started the push toward a new treatment approach that reduced the strict gatekeeping previously commonplace in transgender medicine.

Arriving at the Two Types: Effeminate Homosexuals and Transvestites

In the 1970s, researchers turned their attention to understanding the underlying causes of transsexualism. They had known for some time that their transsexual research subjects bore a remarkable similarity to either effeminate gay men or transvestites, but they still weren’t sure how many distinct types of transsexualism there were.

John Money proposed one of the first two-type taxonomies in 1970, dividing MTF transsexuals into “transvestitic” and “effeminate-homosexual” types[viii].

The homosexual group was gender nonconforming as children, only felt attraction to men, and didn’t experience erotic transvestism. By contrast, the transvestitic group wasn’t solely attracted to men or very gender nonconforming as children, but they did report a history of cross-gender arousal[ix].

Six years later, Peter Bentler proposed a three-type MTF taxonomy that separated transsexuals into homosexual, heterosexual, and asexual groups[x]. Interestingly, none of the asexual group had considered themselves homosexual before surgery, but over half had thought of themselves as heterosexual[xi].

Bentler sought to understand the developmental pathways that led to different transsexual outcomes, as well as “the interrelationship that transsexualism has with transvestism and homosexuality”[xii]. Even though his transsexual taxonomy had three types, he pointed to only two related groups from which they came.

A couple of years later, a pair of Australian researchers—Neil Buhrich and Neil McConaghy—published “Two Clinically Discrete Syndromes of Transsexualism”, a paper that provided some preliminary numerical evidence for the two-type model[xiii].

They divided transsexual participants into those who admitted to past arousal from dressing as women and those who denied it. Those who admitted to prior arousal from crossdressing showed significantly more physical arousal to erotic media with women[xiv]. They were also more likely to have had sex with women, to be married to one, and to be older[xv]. From this pattern, the researchers concluded that MTF transsexuals “can be divided into two clinically discrete groups on the basis of whether or not they have shown fetishistic arousal”[xvi].

Taken together, these papers and studies show that by the 1970s, sexologists were converging on a two-type model of MTF transsexualism in which one type was associated with gender-nonconforming homosexuality and the other with erotic transvestism. These studies were still too small to be conclusive, but that was about to change.

A gender clinic in Canada was using fancy new computer technology to create a database of responses to questionnaires filled out by patients during the intake process. With the help of this computer database, clinicians at the gender clinic within the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry in Toronto, Canada, were about to play a major role in transgender history.

Research at the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry

Throughout the 1980s, researchers at the Clarke Institute made a concerted effort to find out how many types of MTF transsexualism there were, as well as what distinguished them.

In “Two Types of Cross-Gender Identity”[xvii], Kurt Freund and others investigated the relationship between gender patients’ reports of prior arousal from crossdressing and their reports of cross-gender identity. The researchers divided gender patients based on whether they reported prior arousal from crossdressing as well as their reported strength of cross-gender identity. Those who reported continuously feeling like a woman for at least a year were classified as transsexuals; those who reported a lesser degree of cross-gender identity were classified as transvestites or borderline transsexuals[xviii].

Almost all nontranssexual subjects were heterosexual and reported sartorial arousal[xix]. In general, researchers found that past arousal from crossdressing was associated with heterosexuality rather than homosexuality.

More than 90% of transsexuals who didn’t report sartorial arousal were classified as homosexual. However, only about half the transsexuals who admitted to sartorial arousal were classified as homosexual[xx]. Even among homosexual-classified transsexuals, those who didn’t report sartorial arousal were significantly more attracted to men (and less to women) than those who reported sartorial arousal[xxi].

The average age of initial contact with the gender clinic varied too. Averaging just under twenty-six years of age, homosexual transsexuals who denied sartorial arousal were the youngest[xxii]. Transsexuals who reported past sartorial arousal were older: the homosexual group averaged about thirty-two years of age and the heterosexual group about thirty-nine years of age[xxiii]. Overall, youth was associated with homosexuality and no prior crossdressing arousal, while older age was associated with heterosexuality and crossdressing arousal.

This was similar to the patterns found by Australian researchers a few years prior[xxiv]. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that “there are two discrete types of cross-gender identity, one heterosexual, and the other homosexual”[xxv].

At the end of “Two Types of Cross-Gender Identity”, a postscript added that another researcher at the clinic had recently made a similar dataset, and looking at it left the authors with the impression that “the two types are even more distinct”[xxvi]. This other researcher was a newer hire, and he was about to spearhead the MTF taxonomy research at the gender clinic. Before the 1980s were over, he would publish three empirical studies on the subject and ultimately pin down the essential difference between the two types of MTF transsexualism.

His name? Ray Blanchard.

Blanchard’s Transsexualism Research

Although the research published by Blanchard’s colleagues suggested there were two types of cross-gender identity, Blanchard himself didn’t start from that premise. Instead, he referred back to Hirschfeld’s four-type taxonomy separating transvestites into homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, and asexual groups[xxvii].

Blanchard started with these four groups and combined them when evidence suggested they were ultimately the same type. The empirical core of Blanchard’s taxonomy research consisted of three studies, all of which shared some methodology[xxviii]:

The data came from self-administered, multiple choice, paper-and-pencil questionnaires

Patients were asked, “Have you ever felt like a woman?” and those who responded, “At all times and for at least one year” were categorized as transsexual

Patients were sorted into four groups (homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, and asexual) using their responses to the Modified Androphilia and Modified Gynephilia Scales

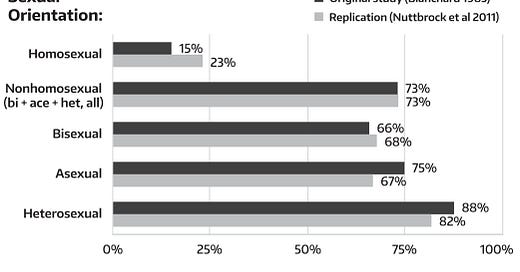

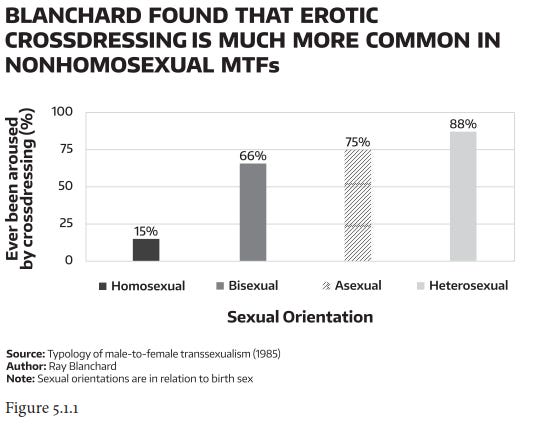

In his classic typology study, “Typology of Male-to-Female Transsexualism” [xxix], Blanchard tallied the number of trans women in each group who reported prior sartorial arousal, and he found drastically different rates for homosexual versus nonhomosexual groups.

This difference suggested a shared underlying etiology for all three nonhomosexual groups, but its exact nature wasn’t yet clear. Still, it had something to do with cross-gender arousal.

In Blanchard’s second typology study[xxx], “Nonhomosexual Gender Dysphoria”, he took the sixteen most representative subjects from each of the four sexual orientation groups and compared them with respect to age and childhood gender nonconformity[xxxi].

The homosexual group reported significantly more childhood gender nonconformity than all three nonhomosexual groups, but the nonhomosexual groups weren’t significantly different from one another[xxxii].

The homosexual group also presented at the gender clinic at a significantly earlier average age (23.6 years) than the nonhomosexual groups, all of which had an average age in their 30s[xxxiii]. This finding that nonhomosexual transsexuals tended to be older matched previous findings[xxxiv].

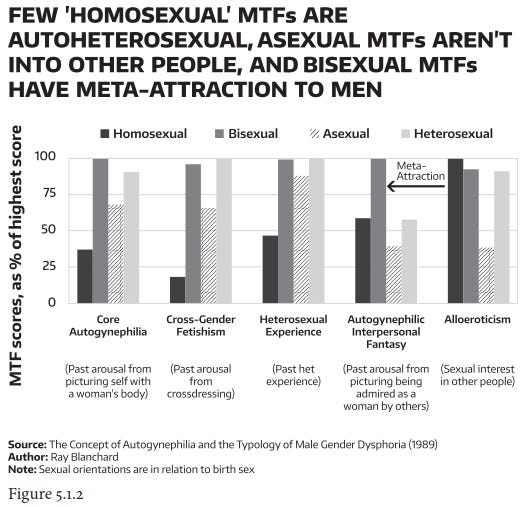

Blanchard’s third and final typology study, “The Concept of Autogynephilia and the Typology of Male Gender Dysphoria”, solidified the two-type MTF typology by demonstrating there were two legitimate types of transgenderism. When people talk about his MTF typology work, they’re often alluding to this study.

In this influential study, Blanchard presented compelling evidence that there were two distinct types of MTF transsexualism, and he also introduced the concept of autogynephilia that tied it all together[xxxv]. He’d solved the typology problem, at least for the foreseeable future.

To create a scale to measure autogynephilia, Blanchard statistically analyzed questionnaire items asking about cross-gender sexual fantasy and sexual interest in other people. He found that they clustered into three main factors[xxxvi], which he developed into psychological scales:

The Core Autogynephilia Scale, which measured past arousal from thoughts of being a woman (core AGP) or having a female body (anatomic AGP)

The Autogynephilic Interpersonal Fantasy Scale, which measured past arousal from the thought of being admired as a woman by others (interpersonal AGP)

The Alloeroticism Scale, which measured sexual interest in other people (allosexuality)

In combination with scales that measured prior arousal from crossdressing (the Cross-Gender Fetishism Scale) and prior heterosexual experience (the Heterosexual Experience Scale), Blanchard created a coherent explanation regarding the factors that set the different nonhomosexual groups apart and what they had in common.

The nonhomosexual groups (heterosexual, bisexual, and asexual) all scored much higher than the homosexual group on measures of Core Autogynephilia, Cross-Gender Fetishism, and Heterosexual Experience, which indicated they were attracted to women and to being a woman far more than the homosexual group[xxxvii].

Scores on the Autogynephilic Interpersonal Fantasy Scale showed that the bisexual group was particularly sexually interested in having their feminine persona admired by others[xxxviii]. Blanchard proposed that this desire for feminine validation was behind their bisexuality. He referred to this gender-affirming attraction to men as “pseudobisexuality”[xxxix].

The asexual group scored almost as high as the bisexual and heterosexual groups on the Heterosexual Experience Scale, but far lower than all other groups on the Alloeroticism Scale[xl]. This result seemed contradictory, so Blanchard checked the clinical charts of some trans women whose questionnaire responses suggested almost complete asexuality, and he noticed that their charts commonly contradicted their questionnaire responses—their testimonies were unreliable[xli].

This finding didn’t rule out the possibility that some bona fide asexuals existed in the asexual group[xlii], but it did show that some gender patients weren’t being 100% accurate in their self-reports, perhaps because strict medical gatekeeping strongly incentivized patients to say what they thought clinicians wanted to hear.

Overall, Blanchard’s three MTF typology studies convincingly demonstrated that all (or virtually all) trans women were either homosexual or autoheterosexual.

These two groups took consistent forms:

The homosexual group was only attracted to men, feminine from an early age, didn’t have a history of cross-gender arousal, and presented at the gender clinic in their mid-twenties on average.

The autoheterosexual group was attracted to women, both men and women, or neither. They were also less innately feminine, had a history of cross-gender arousal, and first presented at the gender clinic in their thirties on average.

This way of sorting trans women—where homosexual trans women are of homosexual etiology and nonhomosexual trans women are of autogynephilic etiology—is often referred to as Blanchard’s transsexualism typology.

Blanchard theorized that asexual trans women lacked interest in other people because their autogynephilia overshadowed their allogynephilia to the point that they lacked interest in women[xliii], and bisexuals were those whose interest in men was a by-product of a desire to have their femininity validated by others[xliv]. Combining these two theoretical insights, it follows that some autogynephilic people will have homosexual partner preferences because their autogynephilia overshadows their attraction to women while also creating a contextual attraction to men.

Seemingly Accurate, but Controversial

Blanchard’s theory neatly synthesized decades of previous research into a coherent picture that finally made sense of MTF transgenderism. Despite its apparent validity, however, many trans women today vehemently oppose this model and critique the underlying research.

They may point out that not all the nonhomosexual groups reported a history of cross-gender arousal, and some of the homosexual group reported a history of cross-gender arousal[xlv]. If Blanchard’s taxonomy was accurate, they may argue, shouldn’t have 100% of the nonhomosexual subjects reported cross-gender arousal and 0% of the homosexual subjects reported cross-gender arousal?

Furthermore, the personal narratives that many trans women have about themselves, their histories, and their motivations do not match up with their conception of autogynephilia.

It’s fair to wonder: if so many trans women disagree with the model, isn’t it likely incorrect?

These critiques are worth addressing, and they raise important questions: Can people be wrong about themselves? And can people understand themselves accurately yet still give unreliable testimony?

The answer on both counts is yes—of course they can. No one has perfect knowledge of themselves or the world around them.

Trans women are as human as anyone else. Just like other types of people, they will respond to incentives and have aspects of their inner world that they don’t want to examine in-depth or share with others.

Just How Reliable Is the Testimony of Gender Patients?

When thinking about Blanchard’s empirical research and the reliability of the self-reports he used, it’s important to consider the context in which he collected that information.

His study subjects were gender-dysphoric patients at a gender clinic. Many of them had to travel great distances to get there and wanted to be approved for cross-sex hormones or surgeries. They knew the clinic didn’t grant permission to everyone who wanted those, so they had a strong incentive to present themselves in a way that would increase their odds of obtaining gender-affirming care.

Blanchard was aware of these incentives, so he conducted two studies to investigate the reliability of their testimonies (and in which ways they skewed, if any).

The first one tested how the normal human tendency to portray oneself in a socially desirable way (social desirability bias) impacted the self-reports given by gender patients[xlvi]. Blanchard found the responses from homosexual gender patients didn’t correlate with measures of social desirability bias, except for the question that asked whether they felt like women[xlvii].

By contrast, the responses from heterosexual gender patients[xlviii] correlated with social desirability bias in a way that skewed toward the conventional picture of an MTF transsexual:

More attraction to men, and less to women

More feminine gender identity

Less erotic transvestism

Based on this finding, Blanchard concluded that nonhomosexual gender patients tended to portray themselves in a way “that emphasizes traits and behaviors characteristic of ‘classic’ transsexualism”[xlix]. Prior researchers had also noted this tendency[l], but now there were numbers to back it up.

In a second study[li] that examined the reliability of testimony from gender patients, Blanchard and his colleagues tested how self-reports of sartorial arousal compared to actual genital blood flow upon hearing spoken narratives of dressing up in women’s clothing.

All groups of heterosexual gender patients in that study—even those who said they’d never been aroused by crossdressing in the past year—had a stronger genital response to narratives of crossdressing than to neutral narratives[lii]. In addition, groups who reported little to no arousal from crossdressing had the strongest erotic response to the meta-androphilic fantasy of having sex with a man as a woman[liii].

Taking people’s testimony at face value is likely to result in a flawed picture, so it’s important to take all types of evidence into account, not just self-reports. When self-reports are used, it’s important to keep in mind the incentives and biases that may affect responses.

Replicating the Two-Type MTF Typology

After Blanchard unveiled the concept of autogynephilia and presented a coherent two-type model of MTF transgenderism, typology research came to a standstill. It took more than fifteen years for other scientists to publish large-scale empirical studies that could either replicate or refute his findings.

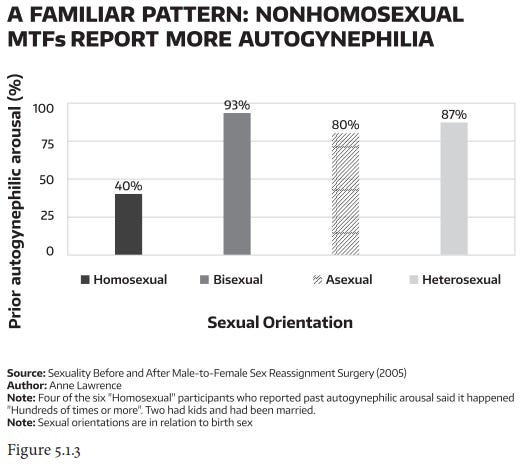

The next study[liv] came out in 2005. It was conducted by Anne Lawrence, an autogynephilic transsexual woman and proponent of Blanchard’s theory.

Lawrence sent a survey to transsexual women who received vaginoplasty from the same surgeon[lv]. The survey asked about their sexual experiences, sexual attractions, and sexual functioning both before and after getting bottom surgery[lvi].

Perhaps because the study participants were all able to afford surgery from an expensive private surgeon, the sample skewed heavily toward nonhomosexual MTFs[lvii]. Based on their reported sexual attractions before surgery, 91% were nonhomosexual[lviii].

In ways that should be familiar by now, the group that reported a sexual preference for men differed noticeably from the groups that reported attraction to women.

This androphilic group reported higher rates of childhood femininity and first wished to change sex at a younger age. On average, they started living as women fourteen years before the other groups[lix]. They were also less likely to report a past of autogynephilic arousal[lx].

When Lawrence sorted study participants by sexual orientation, their rates of past autogynephilic arousal closely resembled the rates of crossdressing arousal that Blanchard had found[lxi]. The vast majority of nonhomosexual MTFs had experienced autogynephilic arousal before, and nearly half of MTFs overall had experienced it hundreds of times or more[lxii].

Dutch Researchers Replicate the MTF Typology

Around the same time that Lawrence’s study came out, so did one from the Dutch gender clinic at the VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam[lxiii]. Researchers investigated whether their gender patients had different rates of transvestic arousal based on their sexual orientation. They categorized patients based solely on self-identification, so their sorting was somewhat flawed, but they nonetheless found the usual types of differences.

On average, the homosexual MTFs recalled more childhood gender nonconformity and applied for surgery about a decade before the nonhomosexual group[lxiv]. They also reported less erotic crossdressing during adolescence (30% of homosexuals versus 54% of nonhomosexuals)[lxv]. Based on these differences, the researchers agreed that there seemed to be two different types of MTFs[lxvi].

Lawrence noticed that a significant fraction of the homosexual MTF group had been married to women or reported past female sexual partners, so she reached out to the authors to see if those subjects were more likely to report sartorial arousal[lxvii].

After recategorizing participants as nonhomosexual if they were previously married or had previous female sexual partners, the Dutch researchers found that the gap in sartorial arousal rates widened: only 14% of the homosexual group reported arousal from crossdressing during adolescence, whereas 53% of the nonhomosexual group still reported arousal[lxviii].

The Most Convincing Replication

In the mid-to-late 2000s, researchers in New York City were working on a study intended to refute (or replicate) Blanchard’s first typology study. This new study used a sample that was three times bigger, more ethnically diverse, and set in the modern day.

It had been more than twenty years since Blanchard’s first taxonomy study. The cultural milieu had changed. Trans people were more accepted than before, and gay marriage was about to become the law of the land in America.

If sex and gender were social constructions and unrelated aspects of oneself, surely this study would turn up significantly different rates of erotic crossdressing than Blanchard found in his study, right?

Nope.

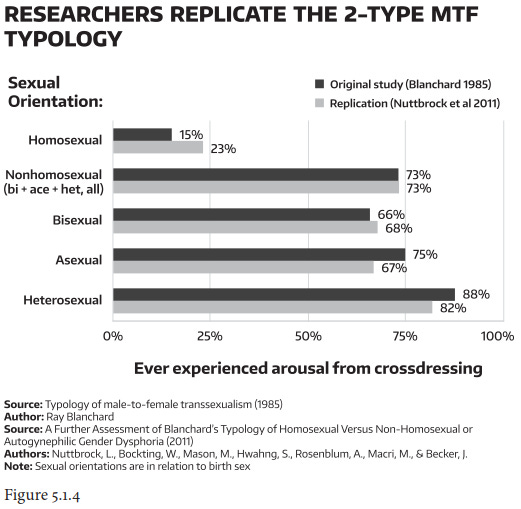

Like Blanchard, these researchers found that 73% of nonhomosexual MTFs reported prior arousal from crossdressing (see Figure 5.1.4). Their homosexual group had a slightly higher rate (23%) than Blanchard’s (15%), but it still fit the same overall pattern[lxix].

Once again, researchers had replicated the results of Blanchard’s first typology study.

I consider this replication to be the most important because the researchers were transparent in their opposition to Blanchard’s two-type model. They extensively downplayed the fact that their study replicated Blanchard’s and made it clear to readers that his theory was politically contentious. In fact, the very first sentence of their summary begins, “In a series of important but now highly controversial articles, Blanchard…”[lxx].

These researchers also brought up a political problem that Blanchard’s research posed: his work was essentialist, and it implied a direct link between sexual orientation and gender identity, which directly conflicted with the orthodox stance within the transgender movement that “sex and gender are separate, socially constructed dimensions of personal identity”[lxxi].

They described the book The Man Who Would Be Queen as “highly polemic” and said that in author Michael Bailey’s framework, “transgenderism was essentially reduced to sexuality”[lxxii].

When discussing their results, they portrayed the association they found between sexual orientation and sartorial arousal as “strong but clearly not deterministic” because the rates of prior sartorial arousal in the homosexual and nonhomosexual groups were 23% and 73%, respectively, rather than 0% and 100%[lxxiii]. They framed this prevalence as “at odds with Blanchard’s predictions”[lxxiv] even though it was fundamentally the same result that Blanchard found.

Despite this misleading framing, the numbers were clear: Blanchard’s findings were replicated a generation later, in a larger and more racially diverse cohort, by a study seemingly conducted with the aim of refuting his findings.

Before any of this research, it was already well established that homosexuality existed, that it was associated with gender nonconformity, and that it had occurred throughout human history. Like homosexuality, autoheterosexuality is perennial. It occurs across generations and has been part of the human story for a long time.

Taken together, these studies present strong evidence that when males have an intense, persistent desire to change sex, they are either homosexual or autoheterosexual.

FTM Typology

There are some telltale signs that autoheterosexuality is also a driver of FTM transsexualism. Search for “euphoria” or “gender euphoria” in an online FTM forum, and you’ll get plenty of results that seem like the autoandrophilic counterpart to male autogynephilia.

It’s super easy to find trans men talking about how they experienced gender euphoria after being addressed as a man, peeing while standing, using men’s hygiene products, seeing themselves after getting top surgery, or wearing a packer. To respect the privacy of the trans men who wrote these accounts, I’m not going to directly cite any here. Just know they exist and are easy to find.

Unfortunately, there hasn’t been much formal research into whether or not trans men are motivated to transition by an attraction to being the other sex. There’s barely any research on transmasculine crossdressers either. Historically, researchers have neglected female sexuality in favor of studying male sexuality, and the lack of research on female autoheterosexuality is just one manifestation of this pattern. Still, there are some signs of autoandrophilia in the official literature.

The study from the Dutch gender clinic[lxxv] that partially corroborated Blanchard’s results found that four of fifty-two homosexual FTMs and one of twenty-two nonhomosexual FTMs reported prior sartorial arousal during adolescence[lxxvi]. Another group of researchers found that seven of twenty-two gay and bisexual trans men (32%) reported prior arousal in response to wearing men’s clothing[lxxvii]. This rate is less than half that reported by nonhomosexual MTFs in prior studies[lxxviii], but it’s not a deal-breaker for the autoheterosexuality hypothesis.

As mentioned previously, females are less likely to have sexual interest in crossdressing, so measuring the presence of autoheterosexuality with questions about crossdressing is especially likely to underestimate its true prevalence in females.

It’s also not yet known why females report less sartorial arousal:

Is men’s clothing less sexually appealing in general?

Is it comparatively easier for people who have a vulva instead of a penis to overlook or otherwise fail to notice the presence of sexual arousal?

Are females less likely to be fetishistic than males, thus focusing more directly on whole bodies and less on specific body parts or the objects around them?

In matters of sexuality, do males have a greater fixation on visual form, while females care more about the quality and nature of interpersonal interactions?

These hypotheses are my current best guesses as to why females and males have such different reported rates of sexual interest in dressing as the other sex, but ultimately the contributors to this disparity are still unknown.

An Exploratory FTM Typology Study

There has been at least one study[lxxix] exploring the possibility that gay and bisexual trans men are of a different type than trans men who prefer women. It came out in 2000, so even though its sample size of thirty-eight was good for its time, it’s small by contemporary standards.

Researchers asked trans men whom they fantasized about then partitioned those who preferred women into the homosexual group and those who were bisexual or preferred men into the nonhomosexual group.

As with MTFs, the homosexual group was less white and reported more childhood gender nonconformity[lxxx]. They also had more interest in women, especially straight ones. But that’s not a surprise: they were assigned to that group based on their preference for women.

By contrast, the nonhomosexual group had a strong preference for masculine sexual partners[lxxxi]. More specifically, they were very interested in gay men. Although they reported moderate interest in other types of sexual partners, gay men appealed to them most of all[lxxxii].

If autoandrophilia drove their desire to transition, we would expect this strong interest in gay men. By partnering with gay men, they can be with their preferred gender and be sure their partner is legitimately attracted to them as men.

In their write-up, researchers suggested that the rarity of strong, persistent nonvanilla sexual interests in females made it unlikely that nonhomosexual FTMs were autoandrophilic[lxxxiii]. Unfortunately, this assumption has kept some leading researchers from realizing that a generalized two-type model can be applied to both sexes.

Is There a Typology for Trans Men?

Even though the two-type typology for MTFs classifies nonhomosexual MTFs as autogynephilic, it has not yet been established through formal research that FTMs can be sorted in the same way.

One potential issue is that female and male sexual orientation appear to function differently[lxxxiv]. When exposed to erotic stimuli in the lab, females show less category specificity in their sexual response than males[lxxxv]. Female sexual orientation also seems more prone to shifting over time[lxxxvi].

Furthermore, some preliminary research suggests transgender identification may spread socially within peer groups, especially among females[lxxxvii]. If further studies account for autoandrophilia and still show a similar pattern, it may be the case that some FTMs are neither homosexual nor autoheterosexual.

However, even if scientists find solid evidence for more than two developmental pathways leading to FTM transgenderism, there is already ample evidence that both homosexuality and autoheterosexuality can motivate females to transition and live as men. The real question is whether there are more than these two types of FTM transgenderism, not whether these two types exist in the first place.

In Sum

Centuries ago, Muslim legal scholars differentiated between two types of effeminate males—those who innately spoke and moved like women yet lacked desire for them, and those who were attracted to women and whose feminine behavior seemed intentional. Both resemble the two known MTF types found in contemporary society.

Magnus Hirschfeld created the term “transvestiten” to describe people who wore clothing of the other sex as valid symbols of inner personality. Based on their sexual partner preferences, he categorized transvestites into four groups: homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, and asexual.

When medical technology advanced to the point that it could help trans people fit into society as the other sex, the category of “transsexual” was born. Harry Benjamin created a six-category scale that spanned the transvestite–transsexual spectrum for the purpose of deciding which patients should get access to surgeries. A patient’s sexual orientation and the intensity of their desire for surgery were the two main criteria considered. Attraction to women disqualified patients from a “true transsexual” diagnosis.

Norman Fisk realized that patients were falsely portraying themselves to medical gatekeepers in order to get hormones and surgeries. However, there seemed to be few regrets, so he reconceptualized the gender situation that clinicians were trying to treat as a type of psychological pain he called “gender dysphoria syndrome”. This new way of thinking about gender issues began to reduce the sexual-orientation-based gatekeeping that had been standard practice in transgender medicine.

In the 1970s, researchers began to converge upon a two-type model of MTF transgenderism in which one type was related to effeminate homosexuality and the other to transvestism. In the 1980s, researchers in Canada utilized new computing technology to conduct the first large-scale quantitative studies of transsexualism, and they, too, found evidence for a two-type MTF model.

After conducting three empirical studies as part of his MTF typology research, Ray Blanchard concluded that homosexual MTFs and nonhomosexual MTFs were of different etiologies. He proposed that nonhomosexual MTFs had an underlying sexuality characterized by arousal at the thought or image of themselves as female, which he called “autogynephilia”.

Later researchers replicated one of Blanchard’s key findings: nonhomosexual MTFs are far more likely than homosexual MTFs to report prior arousal from crossdressing. Even researchers who showed overt hostility to Blanchard’s typology got results that were nearly identical to Blanchard’s. The two-type typology of MTF transgenderism has been replicated several times—empirically, it still stands strong.

There has been little formal research into whether or not the two-type model applies to trans men. Some trans men report prior arousal from crossdressing, which suggests that some trans men are autoandrophilic. Researchers exploring the possibility of a two-type FTM typology found that androphilic-leaning trans men had less childhood gender nonconformity and were especially attracted to gay men—both of which are expected if androphilic trans men are of autoandrophilic etiology.

Speak With Me

Are you an autosexual person who wants to discuss your experiences with someone who actually understands what it’s like? Are you in a relationship with an autosexual person and want to understand them better?

[i] Everett K. Rowson, “The Effeminates of Early Medina,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 111, no. 4 (October–December 1991): 676, https://doi.org/10.2307/603399.

[ii] Rowson, 675.

[iii] Magnus Hirschfeld, Sexualpathologie: Ein Lehrbuch für Aerzte und Studierende (A. Marcus & E. Webers, 1921); Magnus Hirschfeld, Sexual Anomalies and Perversions: A Summary of the Works of the Late Professor Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, ed. Norman Haire (London: Encyclopaedic Press, 1966), 197.

[iv] Aleksandra Djajic-Horváth, “Magnus Hirschfeld,” in Encyclopedia Britannica Online, May 10, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Magnus-Hirschfeld.

[v] Harry Benjamin, The Transsexual Phenomenon, electronic edition (Düsseldorf: Symposium Publishing, 1999).

[vi] N. M. Fisk, “Editorial: Gender Dysphoria Syndrome—The Conceptualization that Liberalizes Indications for Total Gender Reorientation and Implies a Broadly Based Multi-Dimensional Rehabilitative Regimen,” Western Journal of Medicine 120, no. 5 (May 1974): 386–91, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1130142/.

[vii] Fisk, 388.

[viii] J. Money, “Sex Reassignment,” International Journal of Psychiatry 9 (1970): 249–69, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5482977/.

[ix] Anne A. Lawrence, “Sexual Orientation versus Age of Onset as Bases for Typologies (Subtypes) for Gender Identity Disorder in Adolescents and Adults,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 39, no. 2 (April 2010): 517, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9594-3.

[x] Peter M. Bentler, “A Typology of Transsexualism: Gender Identity Theory and Data,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 5, no. 6 (November 1976): 567–84, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541220.

[xi] Bentler, 570.

[xii] Bentler, 567.

[xiii] N. Buhrich and N. McConaghy, “Two Clinically Discrete Syndromes of Transsexualism,” The British Journal of Psychiatry 133, no. 1 (1978): 73–76, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.133.1.73.

[xiv] Buhrich and McConaghy, 75.

[xv] Buhrich and McConaghy, 74.

[xvi] Buhrich and McConaghy, 75.

[xvii] Kurt Freund, Betty W. Steiner, and Samuel Chan, “Two Types of Cross-Gender Identity,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 11, no. 1 (February 1982): 49–63, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541365.

[xviii] Freund, Steiner, and Chan, 55.

[xix] Freund, Steiner, and Chan, 56.

[xx] Freund, Steiner, and Chan, 56.

[xxi] Freund, Steiner, and Chan, 57.

[xxii] Freund, Steiner, and Chan, 56.

[xxiii] Freund, Steiner, and Chan, 56.

[xxiv] Buhrich and McConaghy, “Two Clinically Discrete Syndromes of Transsexualism.”

[xxv] Freund, Steiner, and Chan, “Two Types of Cross-Gender Identity,” 49.

[xxvi] Freund, Steiner, and Chan, 61.

[xxvii] Ray Blanchard, “Early History of the Concept of Autogynephilia,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 34, no. 4 (August 2005): 443, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-005-4343-8.

[xxviii] Ray Blanchard, “Autogynephilia and the Taxonomy of Gender Identity Disorders in Biological Males” (talk, 26th Annual Meeting of the International Academy of Sex Research, Paris, France, June 2000).

[xxix] Ray Blanchard, “Typology of Male-to-Female Transsexualism,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 14, no. 3 (June 1985): 247–61, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01542107.

[xxx] Ray Blanchard, “Nonhomosexual Gender Dysphoria,” Journal of Sex Research 24, no. 1 (1988): 188–93, https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498809551410.

[xxxi] Blanchard, 189, 190.

[xxxii] Blanchard, 191.

[xxxiii] Blanchard, 191.

[xxxiv] Bentler, “A Typology of Transsexualism”; Buhrich and McConaghy, “Two Clinically Discrete Syndromes of Transsexualism.”

[xxxv] Ray Blanchard, “The Concept of Autogynephilia and the Typology of Male Gender Dysphoria,” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177, no. 10 (October 1989): 616–23, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198910000-00004.

[xxxvi] Blanchard, 619.

[xxxvii] Blanchard, 621.

[xxxviii] Blanchard, 621.

[xxxix] Blanchard, 622.

[xl] Blanchard, 621.

[xli] Blanchard, 622.

[xlii] Blanchard, 622.

[xliii] Ray Blanchard, “The Classification and Labeling of Nonhomosexual Gender Dysphorias,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 18, no. 4 (August 1989): 324, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541951.

[xliv] Blanchard, 323.

[xlv] Julia M. Serano, “The Case Against Autogynephilia,” International Journal of Transgenderism 12, no. 3 (2010): 180–81, https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2010.514223.

[xlvi] Ray Blanchard, Leonard H. Clemmensen, and Betty W. Steiner, “Social Desirability Response Set and Systematic Distortion in the Self-Report of Adult Male Gender Patients,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 14, no. 6 (December 1985): 505–16, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541751.

[xlvii] Blanchard, Clemmensen, and Steiner, 511.

[xlviii] Blanchard, Clemmensen, and Steiner, 511.

[xlix] Blanchard, Clemmensen, and Steiner, 513.

[l] Fisk, “Editorial: Gender Dysphoria Syndrome.”

[li] Ray Blanchard, I. G. Racansky, and Betty W. Steiner, “Phallometric Detection of Fetishistic Arousal in Heterosexual Male Cross-Dressers,” The Journal of Sex Research 22, no. 4 (November 1986): 452–62, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3812291.

[lii] Blanchard, Racansky, and Steiner, 459.

[liii] Blanchard, Racansky, and Steiner, 459.

[liv] Anne A. Lawrence, “Sexuality Before and After Male-to-Female Sex Reassignment Surgery,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 34, no. 2 (April 2005): 147–66, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-005-1793-y.

[lv] Lawrence, 151.

[lvi] Lawrence, 152.

[lvii] Lawrence, 162.

[lviii] Lawrence, 153.

[lix] Lawrence, 154.

[lx] Lawrence, 154.

[lxi] Lawrence, 160.

[lxii] Lawrence, 160.

[lxiii] Yolanda L. S. Smith et al., “Transsexual Subtypes: Clinical and Theoretical Significance,” Psychiatry Research 137, no. 3 (December 2005): 151–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2005.01.008.

[lxiv] Smith et al., 155.

[lxv] Smith et al., 156.

[lxvi] Smith et al., 158.

[lxvii] Anne A. Lawrence, “Male-to-Female Transsexual Subtypes: Sexual Arousal with Cross-Dressing and Physical Measurements,” Psychiatry Research 157, no. 1–3 (January 2008): 319, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2007.06.018.

[lxviii] Lawrence, 320.

[lxix] Larry Nuttbrock et al., “A Further Assessment of Blanchard’s Typology of Homosexual versus Non-Homosexual or Autogynephilic Gender Dysphoria,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 40, no. 2 (April 2011): 252, 255, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9579-2.

[lxx] Nuttbrock et al., 247.

[lxxi] Nuttbrock et al., 249.

[lxxii] Nuttbrock et al., 249.

[lxxiii] Nuttbrock et al., 255.

[lxxiv] Nuttbrock et al., 255.

[lxxv] Smith et al., “Transsexual Subtypes.”

[lxxvi] Smith et al., 156.

[lxxvii] Walter Bockting, Autumn Benner, and Eli Coleman, “Gay and Bisexual Identity Development Among Female-to-Male Transsexuals in North America: Emergence of a Transgender Sexuality,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 38, no. 5 (October 2009): 692, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9489-3.

[lxxviii] Lawrence, “Sexuality Before and After"; Blanchard, “Typology of Male-to-Female Transsexualism.”

[lxxix] Meredith L. Chivers and J. Michael Bailey, “Sexual Orientation of Female-to-Male Transsexuals: A Comparison of Homosexual and Nonhomosexual Types,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 29, no. 3 (2000): 259–78, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1001915530479.

[lxxx] Chivers and Bailey, 268.

[lxxxi] Chivers and Bailey, 269.

[lxxxii] Chivers and Bailey, 269.

[lxxxiii] Chivers and Bailey, 275.

[lxxxiv] J. Michael Bailey, “What Is Sexual Orientation and Do Women Have One?,” in Contemporary Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Identities, ed. Debra A. Hope, vol. 54, Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (New York: Springer, 2009), 43–63, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09556-1_3.

[lxxxv] Meredith L. Chivers and J. Michael Bailey, “A Sex Difference in Features that Elicit Genital Response,” Biological Psychology 70, no. 2 (October 2005): 118, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2004.12.002; Meredith L. Chivers et al., “A Sex Difference in the Specificity of Sexual Arousal,” Psychological Science 15, no. 11 (November 2004): 740, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00750.x; Bailey, “What Is Sexual Orientation,” 56.

[lxxxvi] Lisa M. Diamond, Sexual Fluidity: Understanding Women’s Love and Desire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008).

[lxxxvii] Lisa Littman, “Parent Reports of Adolescents and Young Adults Perceived to Show Signs of a Rapid Onset of Gender Dysphoria,” PLoS ONE 13, no. 8 (August 2018): e0202330, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202330.