More Females Are Transitioning

Chapter 5.4 of Autoheterosexual: Attracted to Being the Other Sex

Starting around the years 2005 to 2006, referrals to gender clinics for gender dysphoria began shooting up. Patient demographics have shifted too. Males used to be the majority of referrals, but now females are[i].

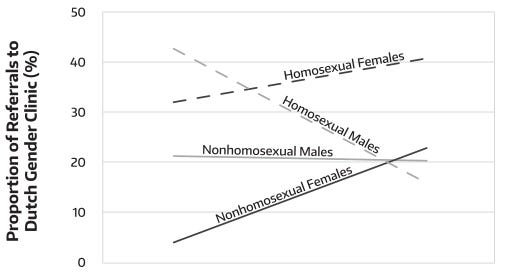

At the Dutch gender clinic, homosexual males went from being the largest subgroup to being the smallest (see Figure 5.4.1). Homosexual females became the largest group, and nonhomosexual females went from being virtually nonexistent to being about as prevalent as nonhomosexual males[ii].

Trends in gender identification also suggest that females are currently more susceptible to developing gender issues. Approximately 75–80% of people with suprabinary gender identities (identities beyond female or male) are of the female sex[iii]. Most transgender-identified adolescents are female too[iv].

Age distributions also reflect the recent surge in transgenderism among females. The 2011 NTDS and 2015 USTS both found that 90% of trans men were younger than forty-five years of age and that people with suprabinary gender identities were similarly young[v].

As seen in Chapter 5.0, females are about half as likely to be either autoheterosexual or homosexual. Since these orientations likely occur at similar rates across generations, these two main causes of transgenderism are unlikely to be the sole contributors to the changing composition of the transgender population. Other factors likely act in tandem with these orientations to create the recent demographic shifts.

Social Media

Widespread adoption of social media began around the same time that gender clinics started receiving more referrals for gender dysphoria.

Myspace started in 2003. Facebook started in 2004 and introduced the news feed in 2006. Twitter started in 2006, Tumblr in 2007, Instagram in 2010, and Snapchat in 2011. Through these platforms, transgender people could share their stories and advocate for themselves at an unprecedented level. These virtual communities also gave gender-dysphoric people access to information that could help them understand their situation.

Less helpfully, social media also enabled people to compare themselves to the misleadingly positive presentations of their peers’ lives. Whitewashed images of happiness and beauty had previously been largely confined to professionally produced media like advertisements, television, and film, but now acquaintances and friends produced them as well, making them seem even more real.

Social media also enabled the spread of a very specific set of postmodern gender ideas which are being inserted into school curriculums, propagated by major nonprofit organizations, and spread by millions of believers through their social media accounts.

Rapid-Onset Gender Dysphoria (ROGD)

Sexual researchers have proposed that some adolescents and young adults who are claiming to be gender dysphoric or transgender are being influenced to do so by social forces[vi]. The technical term for these social forces is “social contagion”, which the American Psychological Association defines as “the spread of behaviors, attitudes, and affect through crowds and other types of social aggregates from one member to another”[vii].

This type of gender dysphoria supposedly affects females more than males. It has been named rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD) because it often appears in adolescents whose parents didn’t notice significant gender nonconformity in their younger years. The parents of these adolescents are often surprised to hear of their child’s gender dysphoria or transgender identity. Many report that prior to this revelation, their child had increased social media usage or one of their friends came out as trans.

Perhaps not coincidentally, ROGD arises during or after puberty—the same age when autoheterosexual gender dysphoria usually manifests.

Lisa Littman conducted the first study exploring the possibility of ROGD by surveying parents who reported that their child had a sudden onset of gender dysphoria during or after puberty[viii]. About 80% of the children were female[ix], and a similar proportion of the parents said their child’s announcement of being either gender dysphoric or transgender caught them by surprise[x].

Most parents said their children were using social media more often just prior to their announcement of gender dysphoria[xi]. After coming out as trans, most of them experienced a boost in popularity within their friend group. An average of 3.5 kids in these friend groups had become gender dysphoric, and in more than a third of friend groups, a majority of the friends became transgender-identified[xii]. Only 3% of parents reported that their child was the first in their friend circle to come out as trans[xiii].

Although would-be transgender people tend to befriend each other, and the cultural environment is becoming increasingly friendly to trans people, these rates of transgender identification within friend groups are absurdly high. The influence of social contagion is definitely worth examining.

On the other hand, the subjects’ rates of homosexuality and nonhomosexuality were similar to the broader transgender population[xiv], which is what we’d expect to see if most of these cases of gender dysphoria were ultimately just cases of homosexual or autoheterosexual gender dysphoria.

Littman’s study didn’t ask parents whether their kids showed any signs of autoheterosexuality, so there’s no way to know how many of these adolescents were autoheterosexual. Still, it’s important to consider the possibility that many cases of rapid-onset gender dysphoria are actually cases of autohet gender dysphoria. Like ROGD, autohet gender dysphoria usually makes itself known during or after puberty, and the announcement of a transgender identity by autohets often comes as a surprise to their friends and family.

Sex, Etiology, and Gender Issues

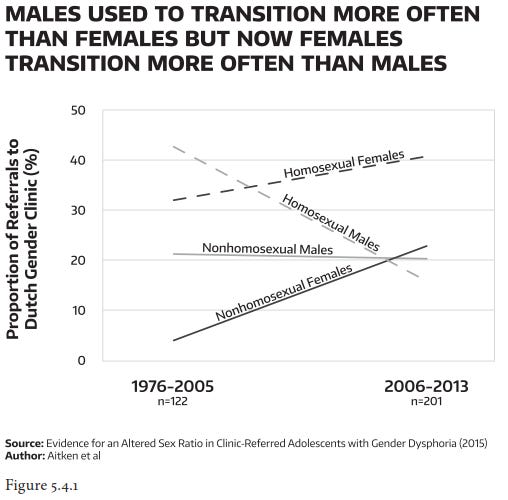

In order to infer which sex and which etiology contributes more to gender issues, I compared the etiology breakdown within the transgender population to that of the broader etiological population from which they come (the combined homosexual and autoheterosexual population).

To estimate the size of the broader etiological population, I combined American estimates of strong same-sex attraction with Czech estimates of strong autoheterosexuality (those featured in Figure 5.0.3). I assumed a fifty-fifty ratio between females and males. I also assumed the prevalence of homosexuality and autoheterosexuality wouldn’t significantly differ between the two countries. Using this method, the broader etiological population made up about 2.9% of the total population.

As expected, the proportion of trans men within the transgender population exceeded the proportion of females in the broader etiological population: being female increased the odds of gender transition. Likewise, the proportion of autoheterosexuals in the transgender population far exceeded their proportion in the broader etiological population, suggesting that autoheterosexuality is a stronger driver of gender transition than homosexuality.

Within the etiological population from which transgender people originate, being either female or autoheterosexual increases the odds of gender transition.

This is especially apparent for people who are both autohet and female: although autohet females are the smallest subgroup within the broader homosexual and autoheterosexual population, autohet FTMs are the second-most common type of transgender person in the US. And data from the 2011 NTDS[xv] and 2015 USTS[xvi] suggest their proportion is increasing. Using the same sorting methodology described in Chapter 5.3, I found that the relative proportion of nonhomosexual FTMs increased 9% between 2008 and 2015.

During this time, the relative proportion of homosexual FTMs stayed constant, nonhomosexual MTFs decreased 4%, and homosexual MTFs decreased 5%. These shifts suggest that more females than males transitioned during this time, and that much of this increase was driven specifically by autohet FTMs.

Why are Autohet FTMs Becoming More Prevalent?

Trans men increasingly understand that their partner preferences don’t impact the legitimacy of their trans identity. Androphilic trans men such as Lou Sullivan were behind this change. However, it took a while for this knowledge to percolate throughout the broader FTM population.

For years, influential researchers such as Blanchard and Bailey expressed certainty that homosexual transgenderism existed in both sexes, but they were comparatively doubtful there was a female counterpart to autogynephilic MTF transgenderism[xvii]. This stance likely kept some autoandrophilic people from realizing they had legitimate gender issues that could be ameliorated through medical transition, thus reducing the number of trans men who sought such treatment.

Another possible contributor to FTM gender transition is related to sex differences in affinity for objects. Females tend to prefer people-centered, relational occupations, whereas males tend to prefer object-centered, technical occupations[xviii]. This greater male affinity for objects also shows up in sexuality: males are more likely to report transvestism or sexual fetishism (sexual interest in nonliving objects or nongenital body parts)[xix].

This sex difference may seem benign at first, but it can have massive consequences for the development and management of gender dysphoria throughout one’s life: object-mediated sexuality offers some protection against gender dysphoria.

Object-Mediated Sexuality Reduces Dysphoria

When early sexologists such as Magnus Hirschfeld and Havelock Ellis analyzed cases of autohet transgenderism, they considered those who eschewed crossdressing to be the most intense manifestations of the orientation. Recall that Hirschfeld described these patients as the “congenitally most strongly predisposed”[xx], while Ellis said they were “less common but more complete”[xxi].

Blanchard found that among gender clinic patients with a history of transvestism, autogynephilia and fetishism were significant predictors of whether they had a constant cross-gender identity or wanted to get sexual reassignment surgery[xxii]. MTFs who admitted to autogynephilia were far more likely to report a cross-gender identity and a desire for surgery. Fetishism had the opposite effect: those who admitted to fetishism were less likely to report a cross-gender identity or a desire for surgery[xxiii]. (This is why the DSM-5 includes the specifiers “with fetishism” and “with autogynephilia” for diagnoses of Transvestic Disorder[xxiv]).

Although transvestism and fetishism are conceptually distinct, both involve the use of objects. Autohets who can derive symbolic worth from clothing or other objects have a tool for attaining cross-gender embodiment that others lack.

However, females tend to show less sexual interest in transvestism or fetishism. Therefore, when comparing autohet females and males whose autoheterosexuality is of similar strength, the autohet females are likely more susceptible to developing strong gender dysphoria.

Psychological Sex Differences and Other Factors

In addition to the previously discussed factors, there are a few more that I suspect work in tandem to increase gender transition and transgender-identification among females:

Psychological sex differences

Postmodern gender ideas

Patriarchy

Females are more likely to be high in neuroticism (tendency to have negative moods)[xxv]. This means that, on average, they are more prone to strong emotional reactions and negative mood states like anxiety, fear, depression, envy, or loneliness.

Females are more susceptible to anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder[xxvi]. They’re also more likely to have obsessive compulsive disorder[xxvii], eating disorders[xxviii], or body dysmorphia[xxix].

In short, females are more prone to negative mood states and more likely to fixate on the state of their body and ruminate about it at length. The ability to compare themselves with peers on social media probably doesn’t help matters either.

It also might be the case that some adolescents transition as a coping strategy for dealing with unwanted emotions. This is another one of the hypotheses proposed by Littman for making sense of ROGD[xxx]. With all the new ideas about gender floating around, it’s inevitable that some people will misinterpret their negative mood states as evidence that they are transgender.

Postmodern Gender Memeplex (the New Gender Ideas)

The bundle of new gender ideas that have spread rapidly and become popular in the past few years are likely increasing the number of people who decide to transition.

Some critics of these new gender ideas refer to them as “gender identity ideology”[xxxi]. While the ideas do often take the form of an ideology, I’d rather call the phenomenon the postmodern gender memeplex. It’s more neutral and descriptive, albeit less catchy.

A memeplex is simply a bundle of ideas or concepts that tend to propagate together as a group. Postmodern thinking entails skepticism toward overarching narratives and the ability to know objective truths, as well as an obsession with the power of language.

One of the foundational ideas within the postmodern gender memeplex is that “gender is a kind of imitation for which there is no original”[xxxii]. Other nonsensical ideas in the postmodern gender memeplex include these:

Sex isn’t binary[xxxiii]

Sex is a label assigned at birth[xxxiv]

“Sex and gender are…separate, socially constructed dimensions of personal identity”[xxxv]

Beliefs like these are emotionally comforting to autoheterosexuals who are wedded to the idea of being the other sex/gender, and it’s to these emotional benefits that these ideas likely owe their staying power.

The postmodern gender memeplex expands the importance of gender and shrinks the role of sex (ostensibly to help trans and gender-nonconforming people). Placing greater emphasis on gender and less on sex makes gender transition seem like a more powerful intervention, so this shift in emphasis likely encourages more people to undergo gender transition.

Patriarchy

Another potential contributing factor behind increased rates of FTM gender transition is patriarchy, the social system that privileges males over females.

Patriarchy is built into our bodies and psychologies. In many primate species, males fight for social dominance among one another and treat females poorly in order to gain access to their reproductive capacity[xxxvi]. This approach represents the optimal mating strategy for many male primates, which is partly why males are bigger and stronger than females.

Some of patriarchy’s downsides can be mitigated by thoughtfully changing human culture (this is the work of feminism). However, patriarchy is not a human invention or a mere social construction. Although feminists are still chipping away at patriarchy, it won’t fully disappear anytime soon.

In addition to this collective approach to curtailing patriarchy, there is also an individualistic approach to minimizing the downsides of patriarchy—FTM gender transition. By medically transitioning, someone born female can be seen and treated as a man instead of as a woman.

To clarify: I am not arguing that females are transitioning solely because of patriarchy, the new gender ideas, or sex-based psychological differences—only that these are potential contributing factors that, in combination, may partially account for recently increased rates of FTM gender transition ever since social media and transgenderism became mainstream. I still think that someone who is neither homosexual nor autoheterosexual is unlikely to undergo gender transition.

It also doesn’t require a stretch of imagination to conclude that social media has influenced the dramatic rise in FTM gender transition. The surge in transgenderism started around the same time that social media really took off, and online platforms are the primary channel through which the new gender ideas have spread. Social media is a powerful conduit for social contagion—we shouldn’t discount its impact on the propensity for gender transition.

In Sum

Several lines of evidence indicate a recent surge in transgenderism among females. Most referrals to gender clinics used to be male, but the sex ratio shifted around 2006. Now, female patients are more prevalent at gender clinics. Most transgender-identified adolescents and most people with suprabinary gender identities are female.

The rise in transgender identification among females happened around the same time that social media really started to pop off (Twitter started in 2006, Tumblr in 2007, and Facebook’s news feed was introduced in 2006). This overlap in timing is unlikely to be a coincidence.

Reports from parents whose children had a sudden onset of gender dysphoria during or after puberty have revealed patterns that suggest transgender identification can spread quickly through friend groups and reach prevalence rates within those groups that far exceed population norms.

By comparing the etiological makeup of the transgender population to the broader etiological population from which it derives, it’s possible to infer that 1) being female is a stronger contributor to gender issues than being male, and 2) autoheterosexuality is a more powerful driver of gender transition than homosexuality. Unsurprisingly, autoandrophilic FTMs are the fastest-growing segment of the trans population.

Historical ignorance of nonhomosexual FTM transgenderism may have reduced the amount of nonhomosexual FTMs who sought medical transition (because they couldn’t see themselves in the transsexualism literature). Object-mediated sexuality can help reduce gender dysphoria, but females are less likely to have interest in object-mediated sexuality. This leaves autohet females comparatively more susceptible to developing autoheterosexual gender dysphoria.

Psychological sex differences and patriarchy both contribute to gender issues in females: females are more susceptible to negative mood states and body dysmorphia, and transitioning to live as a man has more social benefits under patriarchy. Postmodern gender ideas contribute to greater gender transition rates in both sexes. Under the influence of the new gender ideas, adolescents are more likely to think they might be transgender if they don’t like their bodies or their sex traits.

Speak With Me

Are you an autosexual person who wants to discuss your experiences with someone who actually understands what it’s like? Are you in a relationship with an autosexual person and want to understand them better?

i] Kenneth J. Zucker and Madison Aitken, “Sex Ratio of Transgender Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis” (Inside Matters: 3rd Meeting of the European Association for Transgender Health, Rome, Italy, 2019), unpublished data; Madison Aitken et al., “Evidence for an Altered Sex Ratio in Clinic‐Referred Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria,” The Journal of Sexual Medicine 12, no. 3 (March 2015): 756–63, https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12817.

[ii] Aitken et al., “Evidence for an Altered Sex Ratio,” 759.

[iii] Zucker and Aitken, “Sex Ratio of Transgender Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis”; Jody Herman, “LGB within the T: Sexual Orientation in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey and Implications for Public Policy,” in Trans Studies: The Challenge to Hetero/Homo Normativities, ed. Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel and Sarah Tobias (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2016), 172–88; Sandy E. James et al., The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016), https://www.ustranssurvey.org/reports/#2015report.

[iv] Zucker and Aitken, “Sex Ratio of Transgender Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis.”

[v] Jaime M. Grant et al., Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011), 25, https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf; James et al., The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 46.

[vi] Lisa Littman, “Parent Reports of Adolescents and Young Adults Perceived to Show Signs of a Rapid Onset of Gender Dysphoria,” PLoS ONE 13, no. 8 (August 2018): e0202330, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202330; J. Michael Bailey and Ray Blanchard, “Gender Dysphoria is Not One Thing,” 4thWaveNow (blog), December 7, 2017, https://4thwavenow.com/2017/12/07/gender-dysphoria-is-not-one-thing/.

[vii] Gary R. VandenBos, ed., APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2015), 993, https://doi.org/10.1037/14646-000.

[viii] Littman, “Parent Reports of Adolescents and Young Adults.”

[ix] Littman, 7.

[x] Littman, 13.

[xi] Littman, 16.

[xii] Littman, 16.

[xiii] Littman, 16.

[xiv] Littman, 7.

[xv] Grant et al., Injustice at Every Turn, 29.

[xvi] James et al., The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, 59.

[xvii] Meredith L. Chivers and J. Michael Bailey, “Sexual Orientation of Female-to-Male Transsexuals: A Comparison of Homosexual and Nonhomosexual Types,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 29, no. 3 (2000): 259–60, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1001915530479; Bailey and Blanchard, “Gender Dysphoria is Not One Thing”; Ray Blanchard, “The Classification and Labeling of Nonhomosexual Gender Dysphorias,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 18, no. 4 (August 1989): 32–37, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01541951.

[xviii] R. Su, J. Rounds, and P. I. Armstrong, “Men and Things, Women and People: A Meta-Analysis of Sex Differences in Interests,” Psychological Bulletin 135, no. 6 (2009): 891, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017364; Richard A. Lippa, “Gender Differences in Personality and Interests: When, Where, and Why?,” Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4, no. 11 (November 2010): 1098, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00320.x.

[xix] Klára Bártová et al., “The Prevalence of Paraphilic Interests in the Czech Population: Preference, Arousal, the Use of Pornography, Fantasy, and Behavior,” The Journal of Sex Research 58, no. 1 (January 2021): 86–96, https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1707468.

[xx] Magnus Hirschfeld, Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress, trans. Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1991), 183.

[xxi] Havelock Ellis, “Eonism,” in Studies in the Psychology of Sex, vol. 7, Eonism and Other Supplementary Studies (Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company, 1928), 36, https://archive.org/details/b30010172/page/36/mode/2up.

[xxii] Ray Blanchard, “The DSM Diagnostic Criteria for Transvestic Fetishism,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 39, no. 2 (April 2010): 370, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9541-3.

[xxiii] Blanchard, 370.

[xxiv] American Psychiatric Association, ed., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed. (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2013), 702, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

[xxv] D. P. Schmitt et al., “Why Can’t a Man Be More like a Woman? Sex Differences in Big Five Personality Traits across 55 Cultures,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 94, no. 1 (2008): 175, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.168.

[xxvi] Amanda J. Baxter et al., “Challenging the Myth of an ‘Epidemic’ of Common Mental Disorders: Trends in the Global Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression between 1990 and 2010,” Depression and Anxiety 31, no. 6 (June 2014): 505–516, https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22230.

[xxvii] Y. Sasson et al., “Epidemiology of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A World View,” The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58, no. Supplement 12 (1997): 10, https://www.psychiatrist.com/read-pdf/6527/.

[xxviii] Marie Galmiche et al., “Prevalence of Eating Disorders over the 2000–2018 Period: A Systematic Literature Review,” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 109, no. 5 (May 2019): 1402–1413, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy342.

[xxix] Michael S. Boroughs, Ross Krawczyk, and J. Kevin Thompson, “Body Dysmorphic Disorder among Diverse Racial/Ethnic and Sexual Orientation Groups: Prevalence Estimates and Associated Factors,” Sex Roles 63, no. 9–10 (2010): 732, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9831-1.

[xxx] Littman, “Parent Reports of Adolescents and Young Adults,” 33.

[xxxi] Helen Joyce, Trans: Gender Identity and the New Battle for Women’s Rights (London: Oneworld Publications, 2022).

[xxxii] Judith Butler, “Imitation and Gender Insubordination,” in Inside/Out: Lesbian Theories, Gay Theories, ed. Diana Fuss (New York: Routledge, 1991), 21.

[xxxiii] Allison Nobles, “The Social Construction of Gender and Sex,” The Society Pages, November 26, 2018, https://thesocietypages.org/trot/2018/11/26/the-social-construction-of-gender-and-sex/.

[xxxiv] “Sex and Gender Identity,” Planned Parenthood, accessed August 18, 2022, https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/gender-identity/sex-gender-identity.

[xxxv] Larry Nuttbrock et al., “A Further Assessment of Blanchard’s Typology of Homosexual versus Non-Homosexual or Autogynephilic Gender Dysphoria,” Archives of Sexual Behavior 40, no. 2 (April 2011): 249, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9579-2.

[xxxvi] Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, The Woman That Never Evolved: With a New Preface and Bibliographical Updates (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).